The Road to Sustainable Transport Infrastructure: Why cost-benefit analyses need to integrate gender

Cost-benefit analyses (CBAs) are often the guiding principle for making decisions and investments in transport infrastructure. However, this approach rarely considers the fact that people of different genders use and experience transportation in a variety of ways. Illustrated using a case study in Coimbatore, India, this article explores why gender considerations should be included in transport infrastructure decisions and how they could be integrated into the CBA process.

Why Considering Gender Matters

Improved transport systems are key for advancing gender equality. Transport allows people to juggle busy lives, allowing them to move safely and efficiently from their homes to places of education, care, work, retail, health care, and community. Consequently, transport use is gendered: all genders use and experience transportation differently, owing to gender roles, biases, and discrimination, as well as cultural contexts.

Researchers have long documented how women use transportation differently. For example, women tend to have more complex mobility patterns than men, as women often undertake care work and household chores due to the gendered division of labour. Women are also more likely to walk and use public transport and have less access to resources for travel, such as time, private vehicles, or money. Additionally, women face concerns about personal safety and gender-based violence that influence their travel choices, often avoiding public transport or journeys after nightfall.

Despite the fact that women make up about half of the world’s population, their perspectives as transport users and workers, as well as transport infrastructure’s gendered impacts, are often overlooked in transport planning. While some cities have begun implementing gender-responsive transportation plans, this is not the mainstream approach, partly because women lack sufficient opportunities to weigh in on transport-related decisions.

The same applies when considering transport infrastructure investments. Investment choices for large infrastructure projects are usually made based on CBAs—a methodology that rarely accounts for the outcomes for people of different genders. Transport decisions often remain gender-blind, missing the opportunity for advancing gender equality or potential threats to groups already facing structural discrimination and marginalization.

Access to safe and efficient transport is crucial for sustainable development and advancing gender equality. As former United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon states in the Mobilizing Sustainable Transport for Development report:

Sustainable transport is fundamental to progress […] in achieving the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainable transport supports inclusive growth, job creation, poverty reduction, access to markets, the empowerment of women, and the well-being of persons with disabilities and other vulnerable groups.

Currently, only half of the world’s population living in cities has good access to public transport options, and over 1 billion people are unable to reach an all-weather road from where they live. Providing people around the world with the transport they need to thrive will require massive investments over the coming years. The Global Infrastructure Hub estimates that USD 45 trillion will be needed by 2040 for roads and railways alone. For transport investment to fulfil its promise, gender must be better considered in the decision-making process.

Cost-Benefit Analyses and Gender: The early evidence

CBAs are commonly used to inform decisions about transport investments. They can help decision-makers identify the most cost-effective and beneficial transport options and are often legally mandated for large infrastructure projects. To conduct a CBA, transport planners start by defining the project’s scope, costs such as construction and maintenance, and benefits such as reduced travel time and increased safety. Planners then assign each cost and benefit a monetary value, compare the totals to determine whether a project is viable, and then recommend to decision-makers the most effective and efficient investment option.

Integrating gender considerations can help assess gender-specific benefits and adverse effects, providing a more accurate picture of how transport investments affect the diverse needs of all genders.

CBAs are one of many entry points for gender-responsive transport planning. Integrating gender considerations into CBAs can help assess gender-specific benefits and adverse effects while providing a more accurate picture of how transport investments affect the diverse needs of all genders.

Currently, CBAs for transport projects are mostly gender-blind and do not include gender considerations. Specific guidance is scarce, as most resources either discuss transportation’s gender considerations without explaining how project assessments can incorporate them, or these resources may propose improvements to the CBA methodology without paying specific attention to gender.

Work has begun in developing tools and guidance for better integrating gender in these assessments. The Global Infrastructure Hub has developed a free tool to conduct an integrated CBA of bus transport projects that specifically assesses gender impacts. It estimates the environmental, social, and economic outcomes of bus projects, helping stakeholders make more informed decisions in the early planning stages. Crucially, the tool can provide gender- and income-disaggregated results for transit time savings, auto travel time savings, and active transportation benefits from walking and cycling.

The main barrier to mainstreaming genders in CBAs is a prevailing lack of knowledge and evidence on how to do so, making it difficult for planners to make informed assumptions on gender impacts and their monetary values. A 2017 report from the United States Agency for International Development calls on organizations to provide learning resources for modellers, improve the data collection on the topic, and grant flexibility in how analyses capture gendered impacts.

However, it may not always be possible, at first, to integrate gender aspects into quantitative models and CBAs. Experts convened by the International Transport Forum underlined that CBAs are most useful for transport decision making when they deliver the information sought by decision-makers, draw on the best available local evidence, and transparently explain uncertainties and gaps in the analysis. When high-quality data on gendered impacts is lacking and cannot be accurately integrated into a CBA, presenting decision-makers with additional qualitative information on gender considerations is a better approach.

In Practice: Non-motorized transport in Coimbatore, India

Coimbatore has a population of 1.6 million people, making it the second-largest city in Tamil Nadu, India. It faces pressing transport challenges such as traffic congestion, long commutes, safety concerns, and air pollution. Walking and cycling comprise a small proportion of the transport mode shares, while most people use public transport and private vehicles. To address the challenges, the Coimbatore City Municipal Corporation has developed a 15-year Non-Motorized Transport (NMT) plan, which includes 300 km of walking and cycling routes across the city and aims to benefit one million people, especially women, the elderly, and low-income communities, and reduce CO2 emissions. The total investment costs of the NMT network amount to INR 9,895 million (about USD 121 million).

Using our Sustainable Asset Valuation (SAVi) methodology, we analyzed the NMT plan’s potential economic, social, and environmental outcomes. This integrated CBA shows that the NMT network in Coimbatore will provide efficient, safe, affordable, and convenient transport, and improve the last-mile connectivity to public transport. The greatest impact for the city will be the increased road safety, saving USD 395 million in costs from road accidents over the 23-year project period.

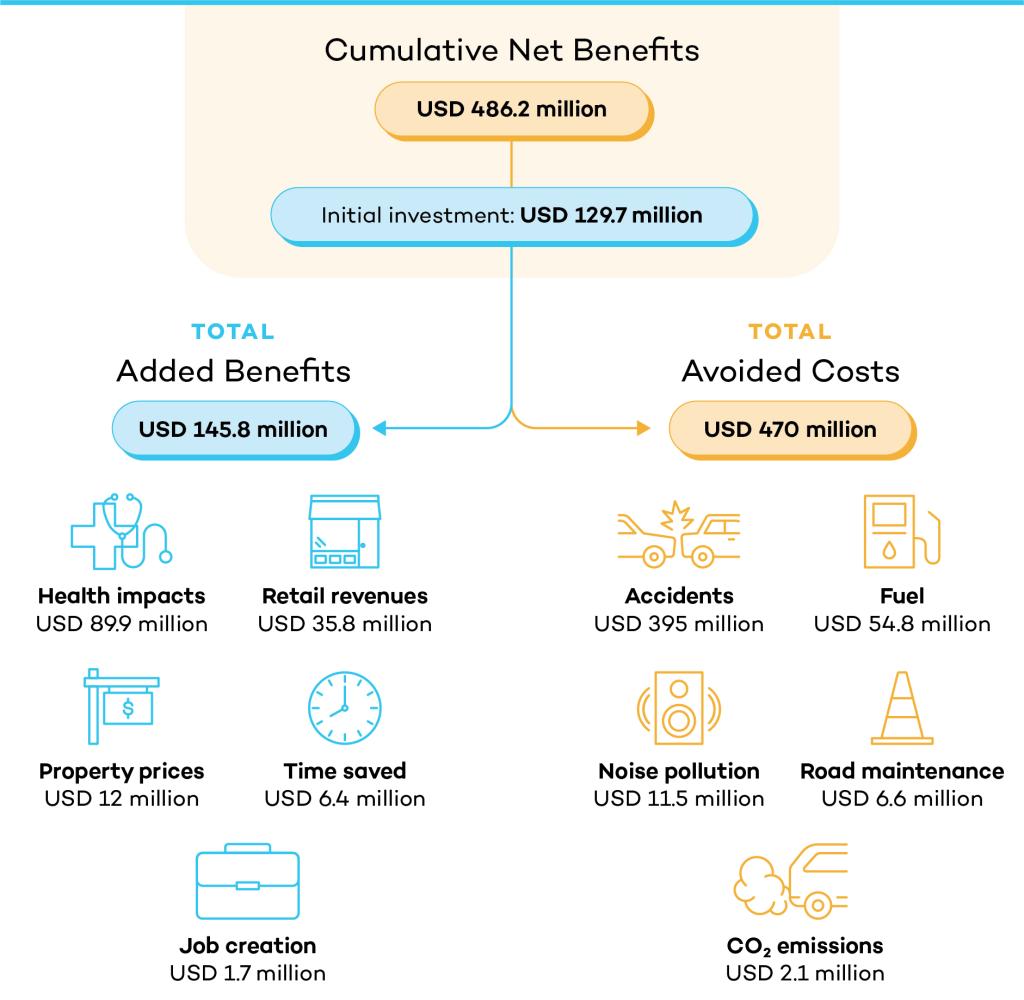

Figure 1 shows the net benefits, avoided costs, and added benefits of the NMT network.

Considering all added benefits and avoided costs, every dollar invested in this NMT network generates between USD 4.75 and USD 4.93 for society. This analysis, however, like most others, did not disaggregate the added benefits and avoided costs by gender.

Gender as Qualitative Dynamics in Systems Mapping

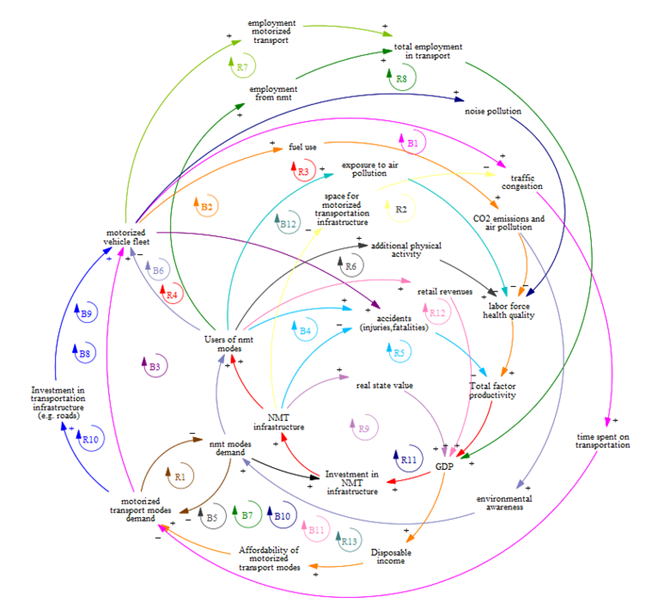

For the analysis, we first developed a causal loop diagram (CLD), which helps visualize the connections between the proposed NMT network and its effects on economic activity, as well as the social and environmental impacts. It is made up of many interconnected factors in the form of loops, and each loop visualizes cause-and-effect relationships that have either a positive (amplifying) effect or a negative (balancing) effect on the other, creating a feedback loop. A CLD enables us to identify the significance of each indicator and provides the basis for quantifying these with mathematical models, assigning them monetary values for an integrated cost-benefit analysis.

Figure 2 shows the CLD that was developed for the Coimbatore NMT network.

The CLD developed for the Coimbatore NMT case study, similar to many such systems maps, did not explicitly consider gender-specific indicators, though the project does have gender-specific dynamics. Incorporating these dynamics into systems mapping, such as a CLD, for transport infrastructure projects can serve as an initial and effective step to ensure that CBAs account for gender impacts.

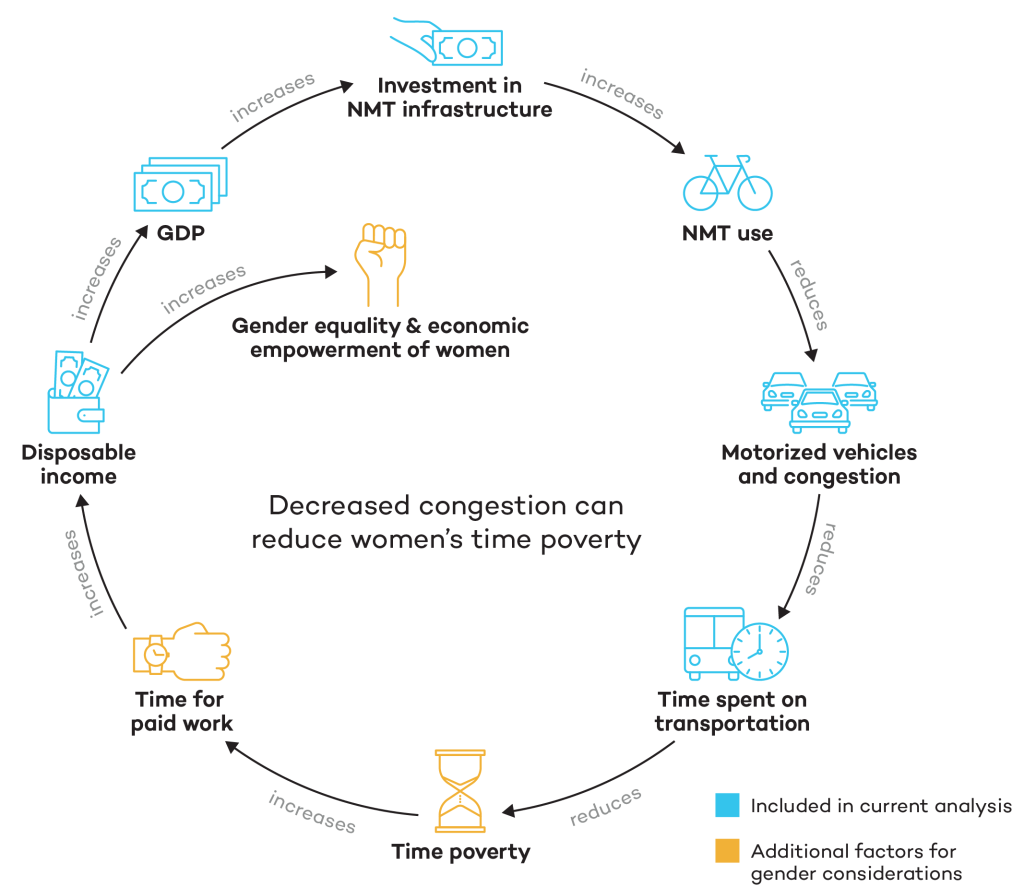

Decreased Congestion Can Reduce Women’s Time Poverty

In Indian cities, women comprise only 18.5% of the formal labour force and spend about 10 times more time on unpaid domestic work than men. They often juggle multiple roles and responsibilities, leaving little time to pursue education, paid work, or personal development. In many cases, women forego job opportunities and favour home-based work due to inefficient transport options preventing them from combining work with caregiving responsibilities World Bank, 2022).

We can adjust the CLD to better reflect the link between congestion, women’s time poverty, and income. Investing in walking and cycling infrastructure increases the use of non-motorized transport modes, reducing the number of motorized vehicles and congestion. Less congestion lowers the time spent on transportation, helping address time poverty, and in turn enabling women to take up paid work and increase their income. This contributes to gender equality and women’s economic empowerment, while boosting GDP and unlocking additional funds for NMT investments.

Increased walking and cycling also helps revitalize local economies. In our CBA of the NMT network, we estimate that retail revenues could be boosted by USD 36 million and property values by USD 12 million. This could help foster mixed-use neighbourhoods that contain a variety of residential, commercial, cultural, institutional, or entertainment areas, allowing women to address all their needs locally, reducing time spent on transportation and thus opening up greater opportunities for pursuing paid work or education.

Figure 3 shows the causal loop for reducing women's time poverty.

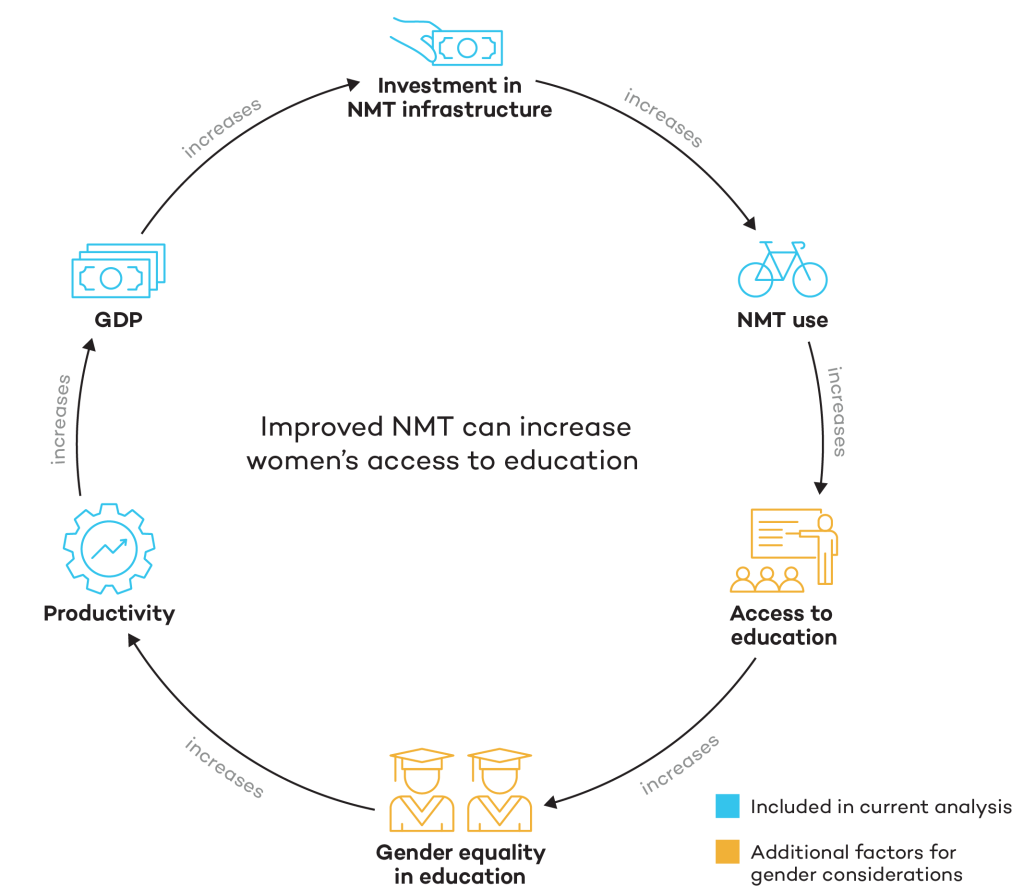

Improved NMT Can Increase Women’s Access to Education

Many low-income women in India struggle to afford fares for public transport and do not have access to private vehicles. Cultural norms also discourage women from cycling and walking in environments that are perceived as unsafe. Together, these factors considerably limit women’s mobility and access to education and economic opportunities. For example, female students in Delhi chose lower-ranked colleges than men to avoid unsafe travel routes, and 52% of women turned down education and work opportunities because of safety concerns.

For Coimbatore, a CLD feedback loop can be refined to consider how the NMT improves access to education, gender equality, and productivity. Investment in the project will increase the use of NMT modes (walking and cycling), boosting access to and participation in education, and resulting in increased productivity and GDP. This GDP growth, in turn, allows for further investment in NMT.

Figure 4 shows the causal loop for improving women's access to education.

Mobility Is Also Affected by Cultural and Societal Contexts for Women

Women use and experience transport differently based on their socio-economic status, ethnicity, caste, education, and age, as well as cultural and societal contexts. Therefore, transport projects should account for these varied contexts to address these diverse needs.

For example, one widespread threat to women in India is the high risk of gender-based violence and harassment in public spaces, with 56% of women reporting that they have been sexually harassed while using public transport. This violence and the fear of violence can lead women to avoid walking, cycling, and public transportation, especially after dark and in crowded situations.

The City of Coimbatore hopes that by investing in the new NMT network, walking and cycling will increase, transportation’s environmental impact will decrease, and women will have greater access to opportunities. However, the risks of gender-based violence and other societal and cultural factors could undermine the NMT network’s potential for improving women’s access to opportunities. To reap the full benefits of the new NMT infrastructure, it needs to be safe and culturally acceptable for women to use the new walking and cycling routes.

To a limited extent, gender-sensitive design and safety policies could increase women’s safety in public spaces and facilitate their access to the new NMT infrastructure. Some measures which have been taken in Indian cities and beyond to increase safety include improved lighting of paths and public transport, emergency response systems, and training for transport employees. However, systemic action is needed from policy-makers and society to tackle gender-based violence, change restrictive cultural norms, and ensure women’s fundamental human right of accessing public spaces.

To capture this gender-specific dynamic in the Coimbatore CLD, we can add a specific indicator about gender-based violence. The below figure shows that safety policies and gender-sensitive infrastructure design could reduce the risks of gender-based violence and improve women’s safety in public spaces, thus supporting women’s access to NMT.

Figure 5 shows how safety policies and gender-sensitive design can increase NMT use.

Using Gender-Disaggregated Data in Quantitative Models

To assess the NMT network’s societal outcomes, we developed a mathematical systems model, building from the qualitative CLD. The Excel-based model quantifies and monetizes key indicators for the CBA—such as income creation, health impacts, and emissions—and, as with the CLD, can be refined further to reflect gender-disaggregated impacts.

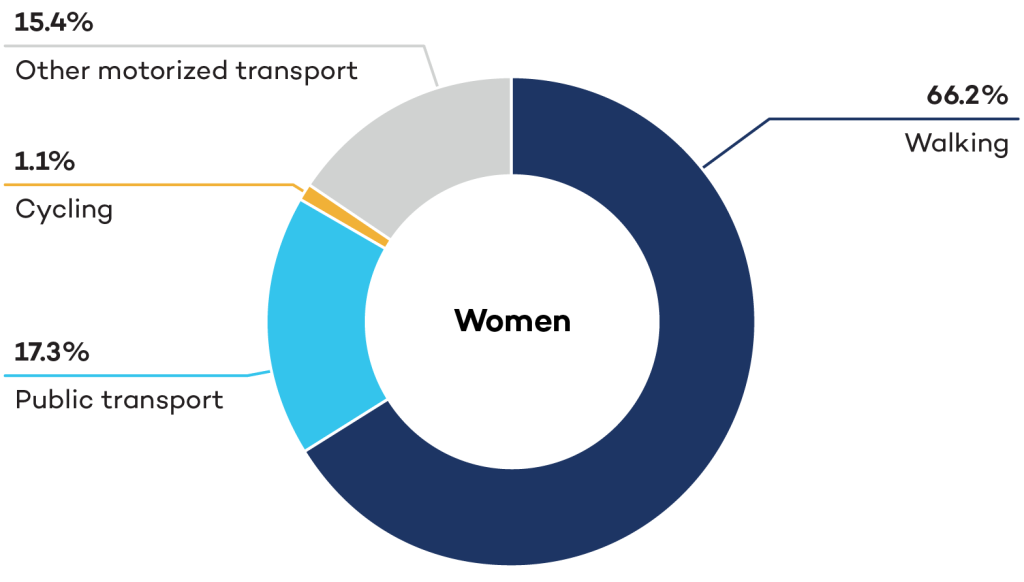

This is important because the causal relationships for men and women may be the same, but the size of the impacts can differ by gender. For example, income influences the affordability of and demand for motorized transport modes for both men and women, but women in India often have less income and more complex journeys. This makes motorized transport less affordable for women, meaning that they rely more heavily on NMT and can benefit disproportionally from the improved infrastructure for NMT and public transport—a lesson that can be learned from other cities, such as Delhi.

Figure 6 shows the transport mode shares for all trips by gender in Delhi, based on Goel et al., 2022.

Gender-disaggregated data is still scarce in the transport sector, limiting the level of detail that mathematical models can achieve. Nonetheless, there are ways to refine the existing mathematical model to better capture gendered impacts related to employment, traffic safety, and health in Coimbatore.

Employment in the Transport Sector

Constructing and operating the NMT network in Coimbatore will create additional jobs and income of USD 1.7 million over 23 years. This value is small relative to the NMT plan’s other benefits, yet the mathematical model could use disaggregated data to capture the transport sector’s large gender gap in employment.

Even within the European Union, with relatively strong norms and guidance on gender equality, women make up just 22% of the transport workforce. The rate of female employment in construction in Asia is only 8%. The vast gender pay gap in India also means that women working in the informal construction sector earn 30% to 40% less than their male colleagues. Integrating such data into the mathematical models and CBA can demonstrate how, unless measures are taken to address these gender gaps, the employment benefits of investing in the NMT will disproportionately benefit men and fail to contribute to gender equality.

Traffic Safety

Avoided traffic accidents are the largest benefit from investing in Coimbatore’s NMT network, saving costs of USD 368 million over the project timeline according to our CBA. Men and women are affected differently by these accidents, which is why the mathematical model should use gender-disaggregated data. Men in India are about six times more likely to be killed or injured in road accidents, while women disproportionately bear the burden after accidents that affect family members, often taking up extra work and care for the injured. The model should aim to consider these gender-specific impacts on productivity and disposable income.

Health Benefits From Additional Physical Activity and Reduced Air Pollution

In India, 44% of women do not engage in sufficient physical activity to maintain their health, as compared to 25% of men. Potential reasons could be that women have fewer work-related trips, cycle less, and do less sports for leisure due to social norms, caste, gender, and socio-economic status.

Improved conditions for NMT can enable greater mobility for women in Coimbatore, promoting increased walking and cycling, particularly for women who previously had limited exercise opportunities. To consider this impact, the mathematical model could use gender-disaggregated data for NMT users, additional physical activity, and impacts on health quality. This would allow for estimating the increased physical activity for men and women and the value of the related health benefits by gender.

Conclusion

Upcoming investments in transport infrastructure present an opportunity for decision-makers and stakeholders to advance gender equality. By focusing on enhancing safety, saving time, and improving women’s access to services and professional opportunities, these investments can have a transformative impact. Leveraging this opportunity requires careful consideration of gender contexts when making decisions about infrastructure investments. One effective approach is to develop more holistic CBAs that capture a systemic understanding of local gender dynamics.

In sum, transport planners and decision-makers can take three actions to better integrate gender in their CBAs. These recommendations are inspired by related research by the United States Agency for International Development that looked at CBAs more broadly.

-

Identify additional gender-specific aspects of transport projects. These dynamics can be mapped in a qualitative way in a CLD. For example, better conditions for walking and cycling can improve women's access to education, which benefits the entire economy.

-

Improve the collection of gender-disaggregated transport data and use it to refine the CBAs. For example, valuations should consider gender differences in transportation modes and travel patterns, disposable income, and employment by sector. Beyond CBAs, collecting gender-disaggregated data also enables evidence-based decisions on improving women's access to safe and secure transport.

-

Quantify and monetize the outcomes of transport investments on people of different genders. For example, job creation in male-dominated sectors such as transport can benefit men more than women and fail to advance gender equality unless additional policies encourage women’s employment. Conversely, reducing congestion can lead to increased income-generation potential for women by reducing time lost in traffic and improving access to job opportunities. Improving traffic safety can generate avoided costs, such as preventing damage to vehicles and infrastructure, and avoided health costs, resulting in greater income generation for women. Furthermore, promoting physical activity can generate specific health benefits for women, resulting in avoided health costs and potentially higher labour productivity and income.

Transportation is a complex topic, and CBAs are just one way to capture women's transportation experiences and needs. Transport planners and decision-makers should actively consider the gendered impacts of transport infrastructure, placing women’s needs as transport users at the core of planning decisions. Empowering women's active participation in the transport decision-making process is crucial. By adopting a gender-sensitive approach to transport planning, it is possible to advance gender equality, creating knock-on effects that benefit the economy, society, and the environment as a whole.

The author would like to thank Liesbeth Casier, Michail Kapetanakis, Benjamin Simmons, Marion Provencher Langlois, Ege Tekinbas, Becca Challis and Sofia Baliño for their work and advice on this article.

Read the full SAVi Assessment of the NMT network in Coimbatore, India here.

Further reading:

-

Global Roadmap of Action Toward Sustainable Mobility, Sustainable Mobility for All

-

Integrating Gender in Cost-Benefit and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis, US Aid

-

Gender Differences in Active Travel in Major Cities Across the World, Goel et al.

-

Gender Gaps in Urban Mobility and Transport Planning, Tanu Priya Uteng

-

Women on the Move: The Impact of Safety Concerns on Women’s Mobility, Ratho & Jain

You might also be interested in

A Sustainable Asset Valuation of Non-Motorized Transport in Coimbatore, India

A Sustainable Asset Valuation (SAVi) of the economic, social, and environmental benefits of a non-motorized transport (NMT) network in Coimbatore, India.

Sustainable Asset Valuation (SAVi) of a Public Bicycle Sharing System in Dwarka, New Delhi, India: A focus on the environmental, social and economic impacts of non-motorized transport infrastructure

This SAVi assessment values the environmental, social and economic benefits generated by a public bicycle sharing system. Its results demonstrate how the transport system delivers to sustainable mobility targets in Delhi.

Building a Climate-Resilient City: Transportation infrastructure

This policy brief examines ways of building resilient urban transportation infrastructure to reduce exposure to natural hazards, decrease potential risks by implementing mitigation measures and enhance adaptive capacity in a changing climate.

Including Women in Sustainable Reconstruction in Ukraine

While Russia's aggression continues, planning for recovery in Ukraine has already begun. To ensure reconstruction is sustainable, women must be leading participants in the post-war recovery.