Tourism Recovery and Resilience in Commonwealth Small States: Driving circular economy pathways post-COVID-19

Kim Kampel from the Commonwealth Small States office in Geneva discusses ways in which circular economy principles and practices can help ensure tourism sectors in Commonwealth Small States (CSS) can recover and thrive in a post-COVID-19 world.

This article was originally published in IISD's Trade and Sustainability Review, Volume 1, Issue 3.

This article highlights strategies that could ensure the resilient recovery of tourism sectors in Commonwealth Small States (CSS) and enable them to differentiate themselves competitively in the new “business-as-unusual” tourism reality post-COVID-19. It focuses in particular on how COVID-19 has precipitated approaches toward a circular tourism services economy, showcasing how many CSS are already incorporating circular economy principles and practices as they reboot their tourism services markets.*

COVID-19 has triggered a cognitive paradigm shift, recognizing the pressing need for people to coexist in balance with an increasingly fragile natural environment rather than destroying it. Accordingly, COVID-19 presents an opportunity for a tourism reset, as governments rethink building sustainable pathways toward recovery to ensure that their tourism sectors are resilient to future climatic events, natural disasters, disease outbreaks, and economic shocks.

At the same time, recovery from COVID-19 coincides with countries looking to transition from a linear economic model of overconsumption and waste generation. The pandemic is accelerating the shift toward circular tourism practices and resource-efficient models as countries reset their tourism strategies to be more sustainable, resilient, and regenerative.

“COVID-19 presents an opportunity for a tourism reset, as governments rethink building sustainable pathways toward recovery to ensure that their tourism sectors are resilient to future climatic events, natural disasters, disease outbreaks, and economic shocks.”

Tourism-dependent economies in some CSS are well-placed to capitalize on this. Many have already adopted innovative, indigenous solutions in response to the decimation of the sector wrought by COVID-19. The benefits include reduced carbon ecological footprints, delivering on climate goals; preserving biodiversity and limiting zoonotic outbreaks; enabling competitive differentiation/diversification in future business models; and building value throughout the tourism value chain, with critical socio-economic spillovers.

There is further scope for such practices to boost and expand trade opportunities in other sectors and attract much-needed investment. Thus, adopting circular practices in tourism gives CSSs a tool to tackle the climate crisis, avoiding the overuse of natural resources and the loss of biodiversity while increasing socio-economic well-being and trade benefits.

How Has COVID-19 Affected CSS Tourism?

The Commonwealth comprises 14 least developed countries (LDCs) and 32 “small” states, designated according to Secretariat criteria (countries with a population of 1.5 million people or less, or countries with a bigger population but share many of the same characteristics). Tourism is the economic lifeblood for many—especially for 25 small island developing states (SIDS). It is one of the primary contributors to job creation, investment, and foreign exchange, spilling over into related sectors such as agriculture, the creative and cultural industries, manufacturing, transportation, finance and insurance, electricity, water, construction, and other services.

For LDCs and SIDS, rapidly growing travel and transport exports respectively accounted for 65% and 85% of their services exports in 2019. Tourism also attracts significant amounts of domestic and foreign investment, accounting for USD 948 billion of capital investment in 2019.

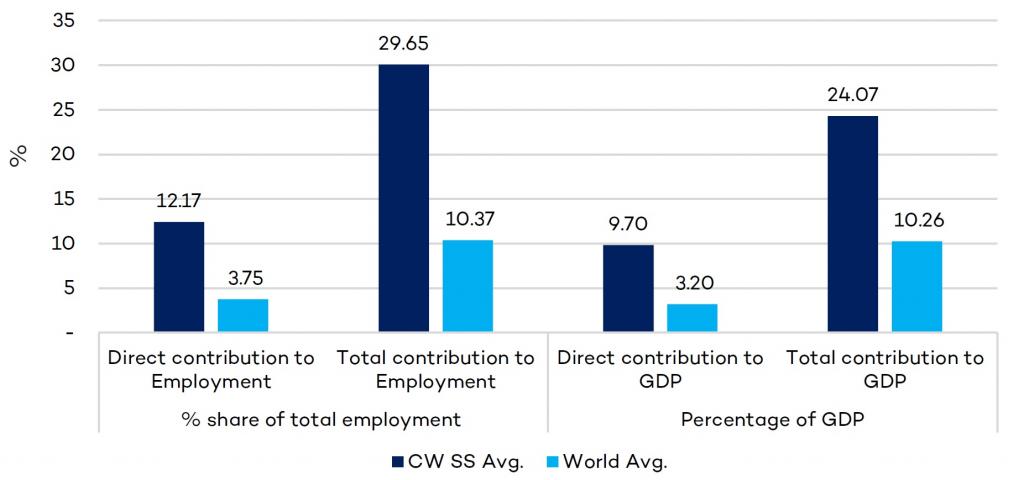

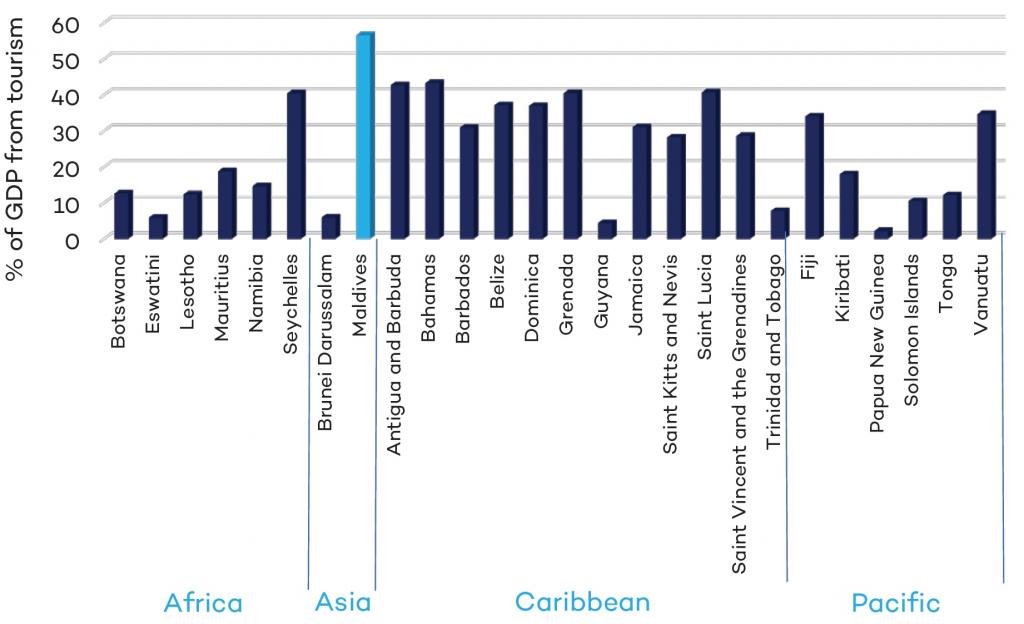

To illustrate the importance of the sector for small states, tourism added 30% on average to total employment from 1995 to 2019, almost triple the world average of 10.4%, and 24% to GDP, more than double the world average of 10.3%. Tourism contributes more than 30% of GDP in 14 of the 32 CSS. This varies from as high as 56% in Maldives, 43% in Antigua and Barbuda and the Bahamas, to 30% in Barbados and Vanuatu.

The WTTC estimates that more than 62 million tourism jobs were lost in 2020—a drop of 18.5%. The full devastating impact of COVID-19 on global travel and tourism last year manifested in the decline in the sector’s contribution to global GDP, dropping a staggering 49.1% in 2020 compared to 2019.

The pandemic has been devastating to the tourism sectors of SIDS and small states, even if the health impact, relative to other economies, has been marginal. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism, economies, and livelihoods in SIDS economies was estimated to have translated into a combined drop in SIDS GDP of 6.9% in 2020 versus 4.8% in all other developing countries (mainly due to global contractions in two ocean economy sectors that are important to many SIDS: coastal tourism and fisheries).

“Adopting circular practices in tourism gives CSS a tool to tackle the climate crisis, avoiding overuse of natural resources and the loss of biodiversity, while increasing socioeconomic well-being and trade benefits.”

CSS face particular challenges that make the free-fall in their dominant tourism sectors even more acute. They are small, lack economies of scale, are remotely situated from major source markets, and face high trade costs. They also have concentrated production and export sectors, fragile public infrastructure, and limited public resources. They are also vulnerable to natural disasters and climatic events. The significant degree of integration of their travel and tourism sectors with other economic activities resulted in economic shocks and losses from the pandemic radiating to low-income informal, community sectors, and vulnerable groups, including women.

Recovery Measures in the Tourism Sector

Based on guiding recommendations and policies issued by global travel bodies—including WTTC and the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UN-WTO)—most countries implemented mitigation, response, and recovery plans for their tourism sectors in 2020. Two broad categories of measures were discernible. The first included short-term, immediate crisis-management responses, including stimulus and relief packages to maintain supply-side capacity and alleviate economic and livelihood losses. The second were measures that focused more on medium- to long-term resilience and recovery of the tourism sector.

Unlike in more advanced tourism destinations, most CSS—many with high debt-GDP ratios—could not rely exclusively on economy-wide or sector-specific stimulus packages and relief measures. Accordingly, sustainable strategies in the medium to long term have been crucial to ensuring the survival of their tourism sectors, as a pathway to economic recovery, especially given the need to maintain the vital socio-economic linkages and spillovers that the sector cultivates.

Early in the pandemic, many CSS governments considered how to make tourism sustainable and resilient against future adverse climatic events, natural disasters, disease outbreaks, and economic shocks. Uncertainties about border reopening and vaccine supply as well as flight disruptions have not prevented many CSS from taking their own measures toward resilience and recovery.

Such supply-side strategies, in advance of the reopening of tourism markets, have included maintaining capacity along the tourism value chain, refurbishing and investing in critical infrastructure, and developing capacity and skills, including rigorous health and safety protocol implementation and training for key workers. The Jamaica-based Global Tourism Resilience and Crisis Management Centre has deployed and scaled up comprehensive, coordinated crisis-management and recovery mechanisms, consolidating ministries, civil society, academia, and the private sector, to drive regional recovery. Vanuatu, in the Pacific, has incorporated informal sector women’s groups in government consultations to guide recovery.

Additionally, enhanced regional collaboration (including harmonized protocols and mitigation strategies) can facilitate subregional supply-side competitiveness and recovery, as recognized throughout the Pacific and Caribbean regions.

"Many CSS governments see the pandemic as an opportunity to link recovery efforts with the global climate agenda."

On the demand side, CSS governments have adopted various recovery strategies to revitalize demand. These include encouraging domestic staycations and intraregional tourism; experimenting with cross-border travel corridors between countries with low infection rates to restore confidence and diversify source markets; offering flexible long-stay options; successfully using virtual and digital marketing strategies to showcase destinations and experiences to stimulate demand and lure back customers; and incentivizing the use of digital tools and remote, paperless technology to future-proof and build resilient pathways for tourism into the 21st century.

Furthermore, the rollout of comprehensive travel health and safety protocols and vaccination strategies (where vaccines are available) as markets reopen and border restrictions ease, combined with innovative, diversified, differentiated tourism offerings, have helped rebuild tourists’ trust and confidence in tourism destination markets, capitalizing on pent-up demand. For example, Maldives recently announced plans for a 3V Tourism Program comprising the elements of “visit, vaccinate, and vacation.”

Such measures make the most of CSS competitive advantages to attract tourists, collectively holding a wealth of biodiversity, wildlife, and cultural assets. Many boast unique geographical configurations that serve as vast natural virus-containment zones, whether in self-contained luxury camps in abundant wildlife areas or on archipelagic island configurations, offering appropriately socially distanced, self-contained getaways in natural, non-urbanized environments to quarantine-weary travellers seeking to escape dense, populated cities. Some small states are proactively transforming these into innovative tourism offerings, rather than allowing tourism assets to degrade as casualties of COVID-19 through wildlife poaching, degradation of marine ecosystems, coastal habitat loss, or deforestation, thereby preventing zoonotic diseases and future pandemics.

Many CSS governments see the pandemic as an opportunity to link recovery efforts with the global climate agenda. They are using blue ocean protection and sustainable, green, eco-friendly strategies to leverage tourism products, simultaneously strengthening resilience to the impacts of climate change, acknowledged as central to the sustainability and viability of the tourism sector.

For some Pacific SIDS, ocean-protection measures have become a major tourism business. They are recognized as complementary strategies to adapt to climate change, simultaneously enabling a thriving tourism economy to support livelihoods and employment while enlisting local, traditional communities as stewards to protect natural resources and biodiversity.

Many of these blue/green economic strategies also embody elements of a circular economy approach to tourism.

The Circular Economy and Tourism

As already mentioned, some CSS are already capitalizing on the trend toward circularity in the tourism sector, incorporating practices that embody the principles of remake, reuse, and recycle in processes or resource utilization practices (the linear economy is known as take–make–dispose, while the circular economy is characterized by borrow–make & reuse–recycle).

How is circularity applied in tourism? As countries reset to a new post-COVID-19 reality, regenerative, circular tourism is gradually changing the conceptualization of sustainable tourism. Unlike the latter, this involves a more long-lasting, proactive, inter-generational approach of resilient tourism, by offsetting the impacts of tourism on the environment, local communities, and the host country as a whole.

In the tourism sector, circular principles have translated into slower forms of tourism, encompassing longer stays, less consumption, low-impact activities, using recyclable processes and materials as well as waste reduction and renewable technologies; ecosystem conservation and mitigating climate or natural disaster risks. This approach also embraces cultural sensitivity, actively contributing to local community-based projects, enabling just distribution of benefits, and ensuring socio-economic spillovers through local value addition and revenue generation throughout the tourism value chain.

The COVID-19 pandemic has catalyzed the various forces driving this evolution to a circular tourism economy. Tourists are increasingly sensitive to the vulnerabilities of destinations, boosting appreciation for ethical, nature-based tourism and the need to leave a positive, responsible, sustainable footprint on the destination. National and global climate imperatives toward sustainable, cleaner methods of consumption/production, as a means of ensuring responsible climate strategies, are also driving a push toward circularity in all business activities. New Zealand recently adopted this approach, unveiling plans to “reset” tourism for a post-COVID-19 world.

In planning post-pandemic recovery, many CSS are also taking circular approaches to tourism. Mass tourism—characterized by packaged, long-haul offerings, with frequent, carbon-intensive chartered and scheduled flight arrivals—historically dominated CSS tourism sectors, especially in SIDS. Popular cruise packages have also concentrated tourism traffic, negatively affecting islands’ energy and resource consumption and pressuring environmental resources, heritage sites, local services, and infrastructure.

At the same time, revenue leakage has been a major obstacle to sustainable tourism growth in many SIDS. Fiji has been proactive in regenerative tourism efforts in the Pacific, allowing tourists to participate in experiential tourism with a community dimension, now aligned to COVID-19 best practices. Many Pacific tourism operators already employ recycling and renewable energy practices that enable them to be self-sufficient from main island grids, protecting ecosystems and managing costs.

“CSS are adopting proactive measures and strategies to lay the basis for sustainable, resilient, future-proofed, and regenerative recovery of their tourism sectors, suitably flexible and agile to adapt to ongoing travel disruptions and evolving health and vaccination protocols.”

Other SIDS have been venturing beyond “sun, sea, and sand” vacations to market experiences involving indigenous communities, including cultural heritage and musical activities. Some also encourage specific tourist-participation projects such as tree planting, turtle protection, and local skills training, though there is scope to improve these efforts and track the uptake levels.

As a direct result of the pandemic, many CSS SIDS now focus on long-stay offerings that reduce the environmental footprint caused by frequent, cheap, long-haul flights. More “digital nomad” or long-stay remote working schemes (targeting already employed business or corporate people) have been rolled out, including in Barbados, Bermuda, Antigua and Barbuda, and Mauritius. These innovative solutions essentially capitalize on the pandemic-induced trend of remote, or office-less, work globally as more people work independently, disconnected from a fixed workplace for indefinite periods, enabling financially self-sustainable remote workers or digital nomads to work in an exotic location for an extended period.

This embodies “slow tourism,” mitigating the health and environmental risks of revolving-door mass extractive tourism, lowering the carbon footprint of frequent long-haul flights; and reducing the ecological footprint of the tourism sector as a whole. At the same time, these new product offerings enable access to new customers in existing or new source markets—and crucially, retain foreign exchange revenue to build local value and linkages throughout the economy, rather than allowing outflows of vital tourism revenues abroad.

In exchange, destinations offer attractive accommodation, facilities, a variety of cultural, adventure, nature-based activities, and high-speed Internet connections. There is also the potential of enhanced trade, investment, and economic benefits flowing from such measures, presenting a path for SIDS to mitigate the competitive disadvantage of being remote from major source markets, as well as offsetting other trade disadvantages.

The Way Forward for CSS Tourism

The ongoing uncertain trajectory of the pandemic, exacerbated by successive waves and the emergence of variants of COVID-19, new outbreaks in the Caribbean region in the first few months of 2021, and uncertainty about vaccine supply and distribution, makes restoration of normal tourism patterns unpredictable. For the immediate future, a key component of economic recovery in CSS will be consistent implementation of vaccination programs; however, this depends largely on supplies reaching smaller developing economies. Recognizing the need to restore tourism’s sectoral competitiveness, the United Nations and the World Trade Organization have called for ensuring SIDS priority access to COVID-19 vaccinations, given the small population size and limited cost compared to the potential benefits of restarting tourism and its attendant value chain activities and socio-economic spillovers.

Nevertheless, CSS are adopting proactive measures and strategies to lay the basis for sustainable, resilient, future-proofed, and regenerative recovery of their tourism sectors, suitably flexible and agile to adapt to ongoing travel disruptions and evolving health and vaccination protocols. In building recovery strategies to innovate and capitalize on their natural assets, governments can play their part in incentivizing, catalyzing, and entrenching existing efforts to ensure the right kinds of sustainable, regenerative, and circular economic recovery, rather than relying on ad hoc, bottom-up approaches.

"For the immediate future, a key component of economic recovery in CSS will be consistent implementation of vaccination programs; however, this depends largely on supplies reaching smaller developing economies."

There is recognition of the need for post-COVID-19 investments and financing to pivot toward resilient, low-carbon, and circular economy recovery strategies. The devastation to the sector wrought by the pandemic has nudged international financial institutions and donor agencies closer to recognizing the economic value and potential of the tourism sector, in particular due to its cascading impact across multiple sectors, communities, and economic activities.

Innovative, circular tourism strategies could be the linchpin to unlock critical investment for the sector and enhance the global trade and investment competitiveness of CSS, including in complementary sectors and activities.

Kim Kampel is a trade adviser on negotiations and emerging trade issues for the Commonwealth Small States office in Geneva.

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

* Previous articles chart potential sustainable tourism recovery strategies post-COVID-19 in CSS as envisaged by the Sustainable Development Goals, by capitalizing on the new normal to reboot their tourism sectors. This paper is based on a presentation for ADB/ADBI/WTO Regional Policy Dialogue on Trade and Sustainability in the Context of COVID-19, in November 2020. It also updates previous papers. Kampel, K. (2020). COVID-19 and tourism: Charting a sustainable, resilient recovery for small states. Trade Hot Topics. Commonwealth Secretariat; Kampel, K. (2020). LDC tourism: Making strides towards sustainable, resilient recovery from COVID-19. Trade for Development News. Circular Economy and Tourism paper, work-in-progress.

You might also be interested in

Avoiding Trade Concerns in the Design of Plastic Pollution Measures

IISD provides insights on aspects of WTO members' plastics that have created friction with trading partners and suggests recommendations for the adoption of such policies in the future.

Securing India's Copper Supply

This policy brief emphasizes the need for India to develop a comprehensive copper strategy.

Microplastics now pervasive in Great Lakes, with 90% of water samples surpassing safe levels for aquatic wildlife: new studies

Data spanning the last ten years reveal that the Great Lakes basin is widely contaminated with microplastics, with potentially dangerous consequences for the wildlife that live within.

Paris Talks a Clear Chance for Canada to Lead on Plastics Pollution

As ministers and policymakers meet in Paris for INC-2, Canada needs to be leading the way when it comes to protecting our environment—and fresh water—from plastics pollution.