The Renaissance of Industrial Policy and Its Articulation With Data Governance

The exponential growth of digital technology in the last two decades has transformed industrial policy. Marilia Maciel, Head of Digital Commerce and Internet Policy at Diplo Foundation, discusses the threats and opportunities of digital industrialization for developing countries.

In the 1990s, as the commercial Internet began to boom, Spanish sociologist Manuel Castells popularized the expression “information economy.” He suggested that competitiveness increasingly depended on the capacity of agents to generate, process, and apply information on a global scale. The amount of added value in products became a function of the knowledge and know-how embedded in them, and charges to use intellectual property flowing from developing to developed countries starkly increased. As Joseph Stiglitz remarked, in such a context, industrial policy should be centred not only around the promotion of technological improvement but also around the creation of “learning societies,” facilitating the diffusion of knowledge from developed to developing countries and the spillover of knowledge from one sector to another in developing countries.

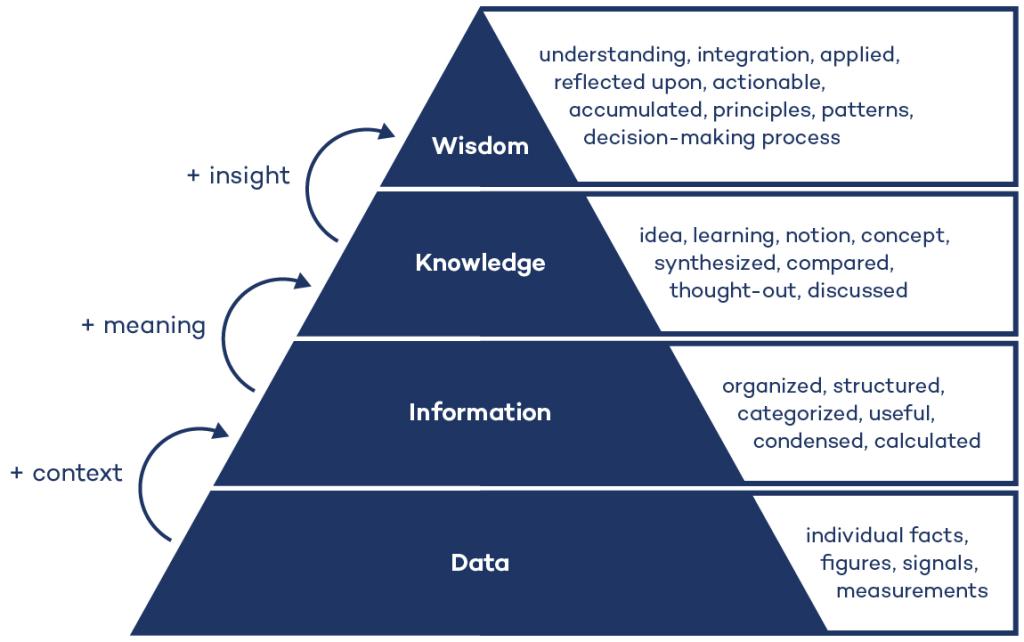

The exponential growth of digitization in the last two decades has meant that most existing information is in digital format. This shift was possible due to the massive adoption of modern computing. Computers operate with digital data—basic pieces of information encoded in a binary format. Data analytics allows computers to correlate data, identify patterns, and make inferences faster and more efficiently than a human being could ever do. Nevertheless, the value of data is only fully realized when data are categorized, analyzed, put into a broader context, and given meaning.

Data are a valuable resource from which information and knowledge are extracted. “It is this knowledge that contains the economic value [of data],” according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, enabling the transformation of traditional sectors (i.e., the digitalization of trade via e-commerce) and the creation of new business models (i.e., platform economy) and new opportunities for industrialization. Industry 4.0 is a fluid expression that may encompass different fields, all of which rely on data, such as precision agriculture, 3D printing, and the cluster of technologies that are part of the Industrial Internet of Things.

Data Scarcity in Developing Countries

One of the main sources of inequality in the digital economy is the uneven distribution of data sets and the resources necessary to produce value and wealth from data. The concentration of data is a notable problem that does not stem from the nature of the resource itself. Unlike the raw materials that serve as inputs to other industries—such as oil or steel—the use of data by one actor does not prevent it from being used by others. Data are also non-depletable; the same piece of data can be used multiple times, in multiple combinations for analysis, without using it up or wearing it out.

Concentration in the data economy can be explained not only by network effects and economies of scope but also by the fact that the data economy encourages specialization. Large firms that have a comparative advantage in data collection use the commercialization of low-priced (or zero-priced) products and services (i.e., access to e-mail services or social media) to collect more data. At the same time, companies exclude third parties from accessing the data they collected, by resorting to technical and legal mechanisms—notably, intellectual property protection.

While developing countries generate large volumes of data, many face data scarcity.

This scenario may put developing countries in a “data poverty trap,” which occurs when firms, industries, or countries cannot take advantage of the initial stages of the economic exploitation of data. In this initial phase, increasing returns from data are very high: more data make a firm more productive, which results in more production and transactions, which generate more data, further increasing the productivity of production processes and data generation in a positive “data feedback loop,” also called the positive loop effect of knowledge creation.

While developing countries generate large volumes of data, many face data scarcity. These low levels of access to data confine them to lower levels of production and transactions and low profits, hindering further data accumulation and knowledge creation. Breaking this cycle is one of the goals of digital industrial policies. Because of the distinct characteristics of this resource (non-rivalrous, non-depletable), a different spectrum of policies, with an emphasis on access to data and data sharing, can be put in place.

Data Governance as a Cornerstone of Industrial Policies

Industrial policy encompasses policies of economic restructuring that shape the behaviour of economic agents toward more dynamic activities, whether or not in the industrial sector as such. They encompass a wide range of areas, such as trade and investment, investment in science and technology, the promotion of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, human resource training, and regional development. Industrial policy requires some form of governmental intervention, which may take place at various stages, from research and development to prototyping, testing, product development, production financing, market entry, and expanded market creation. It presupposes, therefore, that governments have the ability to develop policy and legislate.

For decades, industrial policies suffered a backlash. Liberal theories touted that free markets, competition, and minimal government intervention were the best way to promote innovation. Developing countries that sought to promote industrial policy were labelled protectionist. Today, there is a global shift toward accepting a more proactive stance from governments, especially after the financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic. The current debate on industrial policies is no longer focused on whether such policies are necessary but on how best to implement them, how to mitigate potential protectionist effects, and on the lessons that can be learned from successful industrialization experiences.

There is a global shift toward accepting a more proactive stance from governments, especially after the financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the digital technology sector, industrial policy has presented two interconnected goals: a) to foster the development of the digital economy, which encompasses core activities of information and communication technology (ICT) production (e.g., semiconductors, hardware, software, telecommunications, and information services), as well as business models that did not exist before ICT and that stem directly from the ICT revolution (e.g., digital services and platforms); b) to transform traditional sectors where digital technology enhances productivity, such as trade (e-commerce), health, transport, agriculture, and public services.

Governments can use several tools to promote digital industrial goals, such as resorting to government expenditure, using taxation, and designing the regulatory framework within which digital markets operate. In recent years, developed countries have used all these mechanisms to strengthen their digital industries, contributing to what has been dubbed the renaissance of industrial policy.

The United States—which has been reluctant to implement industrial policy in non-military areas—has committed more than USD 3,000 billion to the Modern American Industrial Strategy, which encompasses specific actions on semiconductor production, development of critical technologies, energy, and developing secure domestic supply chains in critical fields. The semiconductor sector—which will benefit from the CHIPS and Science Act, as well as tax credits—is of fundamental importance to this strategy, as chips are the underlying technology that allows the functioning of hardware (devices) software and data processing.

Data governance is an important counterpart of this industrial strategy. Data flows account for more than 2.4 million jobs in the United States. Data are clearly included within the scope of U.S. trade policy, which seeks to ensure that exports of U.S. digital services continue to grow in global markets through the active promotion of free cross-border data flows. As a consequence, free data flow is a principle enshrined in trade agreements celebrated by the United States and is also advanced in discussions and negotiations in which the United States takes part in the G7, the G20, and the Joint Statement Initiative on e-commerce at the World Trade Organization.

The European Union has also fostered an articulation among data, industrial, and trade policies, and has supported free data flows at the international level via trade agreements. Nevertheless, the European Union is far behind the current leaders in the digital sector—the United States and China—and is seeking to create the internal conditions to be able to compete in the global data market. The EU digital industrial policy aims not only to foster competitiveness, but also to promote an open strategic autonomy by seeking to reduce dependence on foreign supply chains in semiconductors and cloud and edge technologies, for example.

The industrial strategy commits resources to research and deployment of technology in areas such as artificial intelligence, 5G, and data analytics. This strategy is intimately linked to the European Strategy for Data, which aims to create a single market for data capable of ensuring Europe’s global competitiveness and data sovereignty. The strategy emphasizes industrial and public data and represents a shift from an intellectual property-centred approach toward data governance mechanisms that aim to promote data sharing in Europe as a way to unlock its social, economic, and industrial value.

From a normative standpoint, a regulation on a framework for the free flow of non-personal data complemented the General Data Protection Regulation, which guarantees the free flow of personal data in the European Union. Once free flow was established, the Data Governance Act and the Data Act proposal—now under discussion—set forth conditions for data access and data sharing across the bloc. Underlying the regulatory architecture, a data infrastructure is being developed in a bottom-up manner through the GAIA-X project. GAIA-X will link cloud providers through harmonized principles and standards, enabling the development of platforms where companies and citizens will be encouraged to share their data while also retaining control, autonomy, and self-determination.

Data and Digital Industrialization: Threats and opportunities for developing countries

Many developing countries are aware of the importance of data for digital industrialization and development. To pursue these goals, some countries have introduced conditional data transfers or data-localization provisions. In Africa, for example, Rwanda, Nigeria, and South Africa have enacted or are in the process of discussing data-localization measures with the explicit aim of developing their digital industries. At the same time, seven African countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Mauritius, and Nigeria) participate in the Joint Statement Initiative e-commerce negotiations at the World Trade Organization, which aims to put in place a general principle on free data flows.

The data governance landscape across the African continent is highly fragmented. Regulation shows different levels of maturity across countries, different approaches when it comes to cross-border data flows, and little articulation between data, industrial, and trade policies. In spite of that, building a coherent continental approach was never as important as today.

The data governance landscape across the African continent is highly fragmented.

Data flows will be increasingly important as a topic in trade negotiations, but so far there has been little consideration in these talks about the impact of free data flows on development, or about the types of exceptions that would enable developing and least developed countries to use data to leverage their digital industrialization goals. Moreover, from a global perspective, protectionism is on the rise, and developed countries are increasingly associating industrial and trade policies with notions such as reshoring, near-shoring, or friend-shoring of supply chains.

The place of developing countries in a world marked by a conflation between trade and security is uncertain. Predictions about the negative impact that the reshoring of industrial production would have on developing countries are not new. These impacts could be even more significant in the context of current geopolitical tensions.

A coordinated approach could be the best way for developing countries’ data markets to gain scale. In Africa, some opportunities for this coordinated approach are worth noting. The African Union Data Policy Framework, endorsed in February 2022, aims to contribute to the harmonization of data governance policies across Africa and the establishment of adequate data-sharing mechanisms. Working to implement the recommendations made by the Data Policy Framework and tracking their progress will serve as a good compass in years to come. The African Continental Free Trade Agreement provides an opportunity for cooperation on many important aspects of the Data Policy Framework, including increasing interoperability between regulatory frameworks.

There is also an opportunity to establish dialogue and collaboration between developing countries and some developed countries or regions that are also seeking to promote the redistribution of gains in the data economy and enhance economic justice, while providing data access and control privileges to a variety of actors. This is the case of the European Union and also Switzerland, which issued a report in March 2022 on creating trustworthy data spaces based on digital self-determination.

No country has yet found the ultimate recipe for holistic data governance that balances industrial and trade goals with ideals of economic justice.

If regional opportunities, such as the Data Policy Framework and the African Continental Free Trade Agreement, are combined with a dialogue between developed and developing countries, it could be possible to create “learning societies” gathered around data, inspired by Stiglitz’s idea. No country has yet found the ultimate recipe for holistic data governance that balances industrial and trade goals with ideals of economic justice. In this collective learning process, the exchange of successes and failures and the reinforcement of positive spillovers could be key.

Conclusion

The developmental significance of data cannot be underestimated. The capacity to use data to propel economic dynamism has increasingly turned into a competitive advantage not only for companies but also for countries, and it is a source of power in the global political economy. Industrial policies should create both corporate welfare and social welfare. An industrial policy that encompasses data governance as one of its key pillars should foster the opportunity for individuals and communities to have access to this key resource, which has become fundamental to dignified, productive, and creative lives.

A government that does not employ the industrial policy toolset consciously and coherently may not only miss the opportunity of promoting digital industrialization, but it may also be confronted with lower growth and rising inequality.

Marilia Maciel is Head of Digital Commerce and Internet Policy at Diplo Foundation.

You might also be interested in

Rethinking Investment Treaties

International investment treaties and their investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS) system are facing growing scrutiny. But what would an alternative system—one fit for the challenges of the 21st century—look like?

Global Dialogue on Border Carbon Adjustments: The case of Brazil

This report consolidates, analyzes, and presents the views and perspectives of stakeholders from Brazil on border carbon adjustment (BCA) schemes to contribute to the global debate on BCA good practices.

Border Carbon Adjustments: Trinidad and Tobago country report

This report consolidates, analyzes, and presents views and perspectives of stakeholders from Trinidad and Tobago on border carbon adjustment (BCA) schemes to contribute to the global debate on BCA good practices.

Avoiding Trade Concerns in the Design of Plastic Pollution Measures

IISD provides insights on aspects of WTO members' plastics that have created friction with trading partners and suggests recommendations for the adoption of such policies in the future.