Facing the Climate Change Conundrum: A pessimist’s and an optimist’s perspective

We asked a “pessimist” and an “optimist” to share their hypothetical views about climate change futures.

According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), 2016 was the hottest year on record.

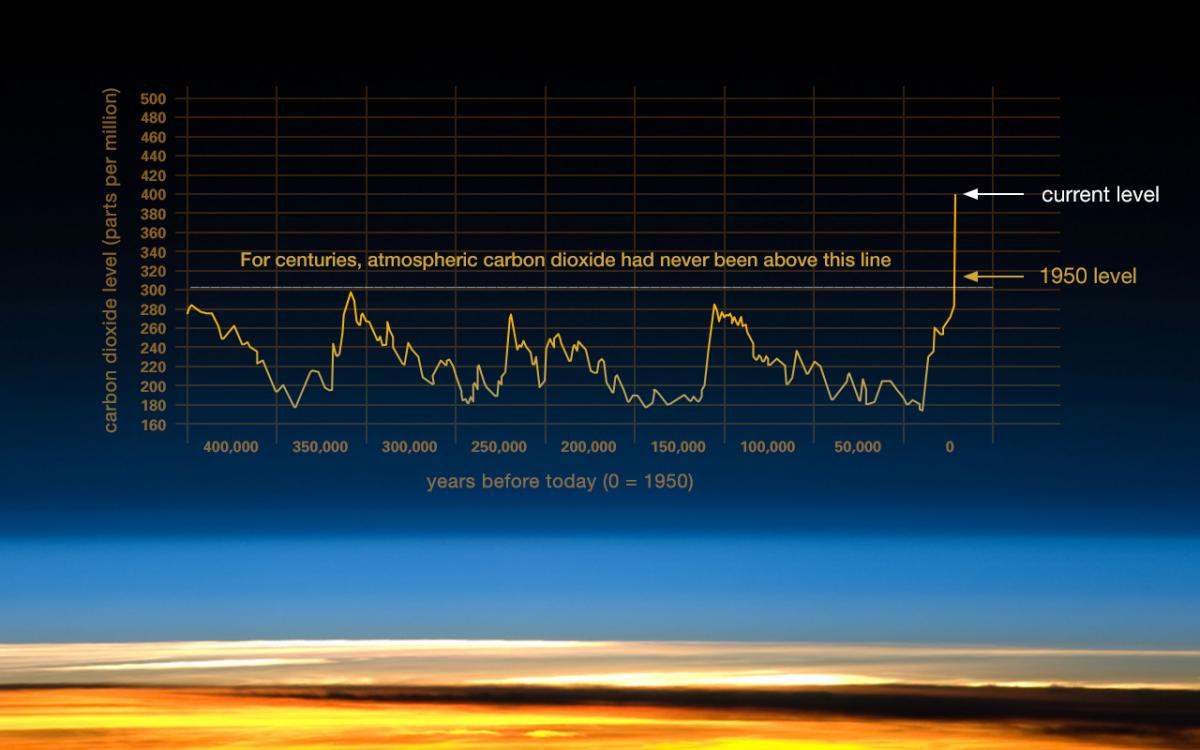

Global average temperature in 2016 was about 1.1°C higher than the pre-industrial period. This may sound like a small increase, but it is not trivial. Scientists are concerned about the speed of the increase: a temperature rise that would typically occur over a few centuries has happened over just a few decades. Since the industrial revolution, we have seen a rise in greenhouse gases exceeding levels not experienced for over 650,000 years. The science is clear—the climate is changing, and this change is caused by human activity.

Source: NASA. Data: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Some description adapted from the Scripps CO2 Program website, "Keeling Curve Lessons."

These changes are troubling, and forecasts are not any better. To stay within climate-safe limits, we must reduce our emissions and limit temperature increases to no more than 2°C while aiming to stay below 1.5°C. If all countries deliver on their current climate pledges, the world will likely experience a 2.9 to 3.4°C average temperature increase. Inaction could cause warming of over 4.5°C. These troubling forecasts are twice the maximum temperatures we have committed to. The next few years will be critical to bending our emissions curve, or it will become incredibly difficult to reduce the pace of increasing emissions.

As researchers and practitioners in the field of climate change, our work is inseparable from scientific evidence and the willingness of governments, the private sector and individuals to take action. For some, it is about preparing for a rather grim future characterized by more frequent and intense climatic impacts. For others, is about building resilience and taking advantage of opportunities despite adversity—it is about hope. For many, the future oscillates between the two.

With the new U.S. administration, the future of climate action is even more uncertain. Will the international community fill the gap and take bolder steps with the potential absence of U.S. leadership on climate? Will market forces and private sector ingenuity get us there?

One of the key conundrums is how we can remain hopeful while facing the growing—and, for some, irrefutable—evidence of change around us.

We asked a “pessimist” and an “optimist” to share their hypothetical views about climate change futures. They provide contrasting approaches to ingenuity, entrepreneurship and social movements, which can be bastions of hope (or a lack thereof) in response to climate change impacts.

Opening Arguments

The Optimist: Being “hopeful” about climate change requires a strong foundation of reality. As stewards of our planet for generations to come, climate science and projections are not just useful but essential to informing and strengthening local, national and international responses to climate change impacts. Climate science is necessary in order to prepare for and respond to present and future challenges, but also to benefit from the opportunities that may emerge with change.

Emerging evidence related to climate change impacts is also revealing creative responses and collaborative efforts to cope with those impacts, and is helping us to understand that, as a global community, we are able not only to survive and recover from shocks, but also to adapt and even thrive amidst change. There are “bastions of hope” emerging constantly around the world—from communities, to governments and organizations, and in particular, as the result of their joint efforts. There is a lot that we can learn about hope from adaptation and resilience-building initiatives in developing countries.

The Pessimist: Being “realistic” about climate change means accepting that we have inflicted irreversible damage, locking in emissions that will stay in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. The best we can “hope” for is avoiding the worst-case scenario. Climate projections show that even if we aim for 2°C, we will still cross that threshold.

Adaptation is accepting the fact that we have changed our climate. Sure, some people can adapt, but many will suffer. Adaptation efforts also fall far short of what is needed for conservation efforts, with an increasing number of species facing extinction as the temperatures rise, all because of human activity. Finally, as much as we can learn from science, we cannot predict how bad it could be. The web of life is complex, and science has not been able to project what the extinction of one species would mean for others. Climate modelling has likely underestimated current emissions and future emissions, as well as runaway impacts of climate change that can put us at a point of no return.

Ingenuity

The Optimist: In developing countries, adaptive responses are often characterized by inventiveness and creativity, which are key to circumventing the challenges posed by limited resources and institutional barriers. In the climate change field, in particular, actions are worth more than a thousand words. Examples of these responses are highlighted yearly as part of the UNFCCC’s Momentum for Change initiative, demonstrating that ingenuity in climate action is making a difference. Among them, a project by a women-led NGO in Morocco is harvesting fog from the air to provide drinking water for people on the edge of Morocco’s Sahara Desert, and, in Seangor, Malaysia, a Connected Mangroves initiative is combining cloud, machine-to-machine and mobile broadband to help the local community to better manage the growth of new mangrove saplings.

The Pessimist: The problem is not on whether we have the ability to come up with technological solutions to reducing emissions, but rather that we do not have the will. It is easier to live within the status quo of a mode of production that capitalizes on short-term benefits at the expense of future generations. Climate change is the tragedy on the horizon and, for many, there is no real benefit to fully considering intergenerational justice. It costs too much, and it hurts too much. How likely are we to give up our current way of living so that future generations have a planet that is livable? Would you start taking public transit? Live closer to work? Change your daily consumption behaviour to minimize your footprint? I would think a majority would have a beef with that (literally, for example, being unwilling to give up GHG-intensive beef). Finally, as the impacts of climate change become more pressing, survival will be the modus operandi for the masses.

Entrepreneurship

The Pessimist: Our societies are based on ever-growing consumption and a profit-driven mentality. Some have suggested, without offering a real and practical alternative, that capitalism as the root cause of environmental destruction. It’s not like socialism has been better at protecting the environment—just look at the cotton production in the Soviet Union that led to the collapse of the Aral Sea. Some refer to electric mobility revolutionizing transportation and the masses giving up their fossil fuel-powered vehicles for electric cars. Let’s be honest: at least in the case of the many, people are not buying a Tesla to save the planet—they are buying it because it’s cool and it’s fast (that is, if they can afford it). Environmentally friendly products have also become products of entitlement, not accessible or affordable, with a yuppie culture that is fonder of the label than the action.

The Optimist: The sustainability of climate change strategies is a crucial component in the achievement of a resilient future. New forms of entrepreneurship suggest that it is possible—and increasingly necessary—to combine adaptive responses with income generation opportunities. For example, the Women’s Empowerment for Resilience and Adaptation Against Climate Change initiative has formed an “association of women-led groups that collect individual-savings of at least USD 1 once a week to generate a pool of funds, from which women borrow and invest into income-generating activities that address climate change. This initiative also empowers women [to] undertake land planning, agro-forestry and soil conservation practices and use energy saving stoves.”

Social movements

The Pessimist: Organizing the majority to act on climate is a futile act. Sure, you’ll see a protest here and there with possibly a visible turnout, but don’t expect to see a movement that lasts the life of an election cycle. They come and they go. And when they come back, you’ll see the same people, over and over again. Finally, ask the masses whether climate is changing and they will likely say “yes.” But ask them whether they will change their behaviour, especially if it costs them, they would likely say “no.” After all, it is easier to pass the cost down to future generations than to be responsible for one’s own actions (and it’s cheaper for the polluter).

The Optimist: There is growing evidence of the power and the potential of social-driven change in the climate change field. Although changing behaviours and perceptions of risk is a long-term process, there are collective efforts emerging around the world. In Australia, women are building a movement to take action on climate change in their households, workplaces and communities. The organization 1 Million Women aims at getting one million women to pledge to take small steps in their daily lives that save energy, reduce waste, cut pollution and lead change. There are increasing examples of the use of social media (Facebook, Twitter) to organize and mobilize citizens for disaster risk reduction, early warning and response.

Concluding Remarks

The Pessimist: Climate is changing and the human species is responsible for it. Without a doubt, we will live in a very different world as we age, and the world we pass on to future generations will not be a pretty one. The question is not whether we can keep within a climate-safe limit—we should find every opportunity to demand that our politicians take action and raise ambition. That said, we need to act on climate not because politicians will act to keep the world within climate-safe limits, but because giving up is not option. We must avoid the worst case of a world in which climate change exceeds 2, or 3, or 4+ degrees Celsius.

The Optimist: To date, 126 parties have ratified the Paris Agreement. Change is already underway. Being hopeful is not at all about denying or minimizing the role of climate change science. It is about understanding it and using it to shape our future, with the conviction that we still can—and will—make a positive impact on the lives of the most vulnerable. It is about owning the consequences of our actions on the environment, on each other and on future generations. It is about constantly recognizing, learning from and being inspired by emerging “bastions of hope.” It is about engaging in a constructive dialogue with the pessimists and the skeptics, and meeting somewhere in the middle in order to enable action and change.

#ClimateChangeHope

#ClimateChangeDespair

#SomewhereInTheMiddle

You might also be interested in

What’s Next After UNEA-6: Why “synergies” is more than a buzzword

In an era marked by escalating environmental challenges and geopolitical tension, the Sixth United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-6) called for more cooperation to tackle the triple planetary crisis.

UNFCCC Submissions Tracker

Tracking and sharing opportunities for stakeholders to give input to the UN climate change negotiations.

The State of Global Environmental Governance 2023

In global environmental talks in 2023, the focus across nearly all issue areas was funding implementation and reviewing performance.

National State of the Environment Report: Uzbekistan

The National State of the Environment Report (NSoER) is a comprehensive document that provides a snapshot of current environmental trends in Uzbekistan's socio-economic development for citizens, experts, and policy-makers in the country of Uzbekistan.