What the World Learned Setting Development Goals

Still Only One Earth: Lessons from 50 years of UN sustainable development policy

The Millennium Development Goals taught us that having a measurement framework for development promotes monitoring and increases accountability. Despite the world being "off track" to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, they may offer the best option to coordinate a global response to COVID-19, reduce the worst impacts, and “build back better.” (Download PDF) (See all policy briefs) (Subscribe to ENB)

With a thunderous standing ovation on 25 September 2015, all 193 United Nations Member States adopted “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” The heart of the 2030 Agenda is its set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a universal set of interrelated and indivisible goals, targets and indicators balanced between the three pillars of sustainable development—social, economic, and environmental—that seek to address the global challenges we face. Addressing the UN Sustainable Development Summit, then UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said, “The Agenda you are adopting today… embodies the aspirations of people everywhere for lives of peace, security, and dignity for a healthy planet. Let us today pledge to light the path to this transformative vision.”

The roots of the SDGs can be traced back to the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden. This marked the first time a UN conference addressed the relationship between humans and their environment. The Conference initiated a global reflection about the need to balance environmental conservation and human development, establishing the foundation for the concept of sustainable development.

Over the past fifty years—through the 1987 Brundtland Commission Report, Our Common Future, and Agenda 21 in 1992, to the 2000 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), The Future We Want in 2012, and ultimately, the SDGs in 2015—sustainable development has evolved beyond environmental protection, social development, and economic development. The vision of a truly sustainable world now encompasses intergenerational and social justice, poverty and hunger eradication, protection of human rights, gender equality, resilience to climate change, sustainable consumption and production, peace, governance, and partnerships. Perhaps as significant, this expanded vision for a sustainable, just world is now translated into measurable goals, targets, and indicators.

Responding to Development Challenges with the Millennium Development Goals

In 2000, a momentous turn of the Gregorian calendar gave the UN system and world leaders a catalyst to revise the terms of global cooperation (Kamau, et al. 2018, p.22). The UN General Assembly (UNGA) convened the Millennium Summit in September 2000, where all 193 Member States adopted the Millennium Declaration, a statement of values, principles, and objectives for the twenty-first century.

The Millennium Declaration responded to many of the world’s foremost development challenges as they appeared in 2000. Most targets in the Millennium Declaration were not new, but derived from the UN global conferences of the 1990s as well as international norms and laws.

After the Millennium Summit, the UNGA adopted resolution 55/162, which requested the UN Secretary-General prepare a roadmap to implement the Millennium Declaration. The resulting eight MDGs and eighteen targets represented a partnership between developed and developing countries “to create an environment—at the national and global levels alike—which is conducive to development and the elimination of poverty” (UN General Assembly, 2001, p.55).

Then UNDP Administrator Mark Malloch-Brown, who developed this roadmap, argued the MDGs melded:

- a human rights-based approach embodied in the UNDP Human Development Report;

- a World Bank pro-market structural adjustment strategy; and

- the target-setting mindset of the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (Tran, 2012).

The MDGs were the first UN development goals that were time-bound. Among other things, countries agreed to halve poverty levels, reduce maternal mortality by three quarters, and under-five child mortality by two thirds by 2015. Over their fifteen-year lifespan, they became the world’s central reference point for development cooperation.

Following the introduction of the MDGs, total official development assistance grew from USD 71 billion in 2000 to USD 124 billion in 2014. The goals gave the international community something tangible to rally around and signaled what could be done with a set of goals (Kamau, et al., 2018, p.24).

But the MDGs did not recognize the multidimensional nature of poverty. They did not address factors that contribute to global poverty, including war and political instability, discrimination and social inequality, vulnerability to natural disasters, absence of rule of law, and corruption. Nor did they address the environmental causes of poverty. They did not consider stakeholder input, limited gender equality to access to education for women, referred to a limited number of healthcare issues, and only spoke about the achievement of primary education.

Despite the limited scope of the MDGs, by the end of 2015, there was marked progress: a significant decline in extreme poverty, the proportion of undernourished people in developing countries, the global under-five mortality rate and maternal mortality ratio, and HIV infections. Yet progress was uneven across regions and countries, leaving many behind (Kamau, et al., 2018, p.27). According to the 2015 Millennium Development Goals Report the percentage of people living in extreme poverty and of underweight children did not drop as markedly in Southern Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. One in eight people remained hungry and 58 million children remained out of school.

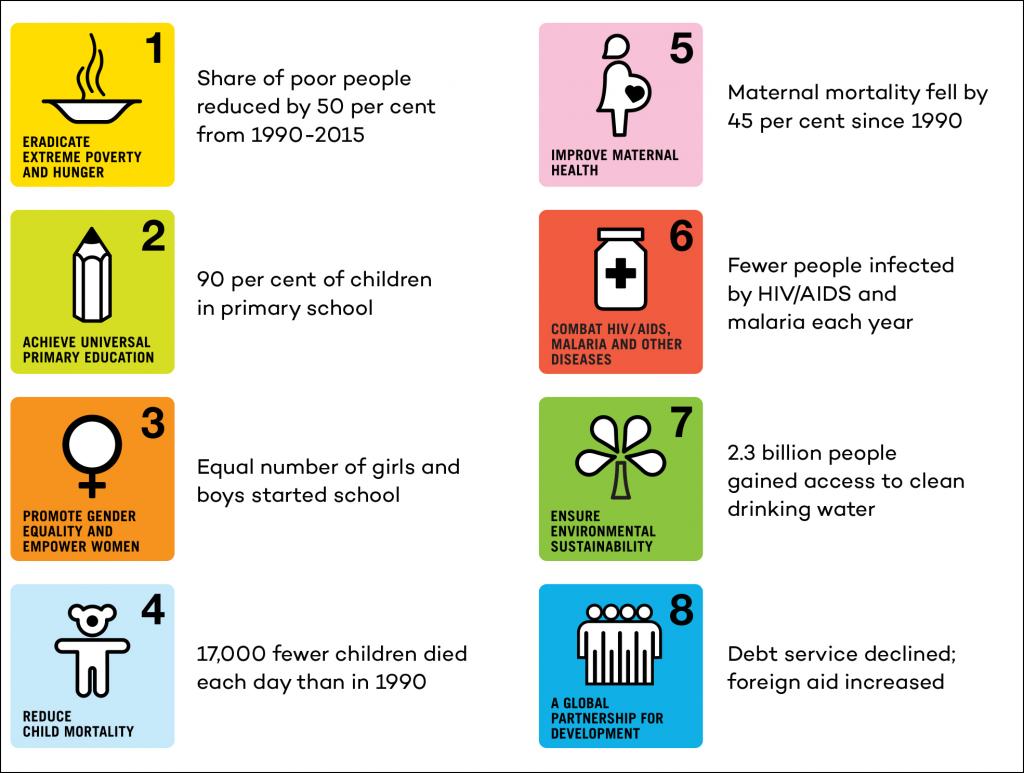

The Millennium Development Goals

By 2015, all UN Member States agreed to:

- Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- Achieve universal primary education

- Promote gender equality and empower women

- Reduce child mortality

- Improve maternal health

- Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

- Ensure environmental sustainability

- Develop a global partnership for development

From the MDGs to the Sustainable Development Goals

In 2010, at a high-level meeting of the UNGA to review MDG implementation, governments recognized the need to look ahead and start thinking about ways to advance the UN development agenda after the MDGs expired in 2015 (Chasek et al., 2016, p.8).

At the same time, Brazil proposed convening a conference to mark the twentieth anniversary of the 1992 Rio Earth Summit and take stock of progress. The UNGA adopted resolution 64/236, which called for the UN Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro in June 2012. The objective of the Rio+20 conference—as it came to be known—was to “secure renewed political commitment for sustainable development, assessing the progress to date and the remaining gaps in the implementation of the outcomes of the major summits on sustainable development and addressing new and emerging challenges.”

Development is not sustainable if it is not fair and inclusive. And people are rightfully questioning a world where a handful of men... hold the same wealth as half of humanity.

As Rio+20 preparations were underway, Colombia proposed that one outcome from the conference could be the development of a set of goals to revamp the MDGs (Chasek et al., 2016, p.8). After months of informal discussions, the idea gained support and was eventually included in the final draft to be adopted in Rio. The outcome document, The Future We Want, recognized the need to develop a series of goals, targets, and indicators useful for pursuing focused and coherent action on sustainable development (paragraphs 245-251). These goals were to be action-oriented, concise, aspirational, global, and universally applied to all countries. Paragraph 248 called for an inclusive and transparent intergovernmental process to develop the goals, open to all stakeholders in the form of an “open working group” (OWG).

The OWG held thirteen sessions from March 2013 to July 2014 to develop the SDGs and targets, with inputs from academia, think tanks, civil society organizations, the private sector, and UN agencies. Simultaneously, there were consultations with civil society around the world to define sustainable development priorities and feed this into the OWG’s work. Ultimately, the OWG recommended a set of seventeen goals and 169 targets to the UN General Assembly.

The first six SDGs reinforced and expanded specific targets from the MDGs. Goals 7-10 expand the MDG agenda and address the root causes of poverty and inequality, as well as the linkages among the economic, social, and environmental pillars of sustainable development. Goals 11-15 look at the impact humans have on the natural environment and how this has affected both social and economic development. The final two goals create the enabling environment to achieve sustainable development.

In September 2014, the UNGA adopted resolution 68/309, welcoming the report of the OWG and deciding the SDGs “shall be the main basis for integrating sustainable development goals into the post-2015 development agenda.” This resolution ensured the SDGs would replace the MDGs. The UNGA also established an intergovernmental negotiating process to agree on an outcome document for the upcoming UN Sustainable Development Summit, which would include a declaration, the SDGs and targets, means of implementation, and follow-up and review. Negotiations began in January 2015 and continued for eight sessions, concluding in July 2015 with agreement on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—just in time for the September summit.

During the negotiations, participants had to keep an eye on two parallel processes that had a direct impact on their work. One was the climate change negotiations under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Paris Agreement was scheduled to be adopted in December 2015, just a few months after the Sustainable Development Summit. Thus, the 2030 Agenda had to balance the needs of countries that wanted stronger language on climate change with those who did not want to prejudge or prejudice the Paris Agreement negotiations (Kamau et al., 2018, p.224).

The second was the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, which was taking place in Ethiopia in July 2015, during the negotiations on the 2030 Agenda. Many wanted the outcome document, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA), to serve as the means of implementation for the 2030 Agenda and launch a renewed and strengthened global partnership for financing people-centered sustainable development (Kamau et al., 2018, p. 225).

The Sustainable Development Goals

By 2030, UN Member States agreed to:

- End poverty in all its forms everywhere

- End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture

- Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

- Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

- Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

- Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all

- Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all

- Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

- Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation

- Reduce inequality within and among countries

- Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable

- Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

- Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

- Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development

- Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss

- Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels

- Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development

Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

The UN Sustainable Development Summit convened in September 2015, with the participation of approximately 160 Heads of State and/or Government. The UN charted a new era for sustainable development with the adoption of “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” This Agenda provides a roadmap to ending global poverty, building a life of dignity, and pledges to leave no one behind. It is people-centered, grounded in human rights principles, instruments, and agreements, and recognizes the crucial role of achieving gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls in the realization of sustainable development. The Agenda seeks to build partnerships, share prosperity, build peace, and protect the planet for the benefit of present and future generations. It also establishes a periodic follow-up and review at all levels to ensure implementation stays on track. The UN High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF), which was established by the UN General Assembly after the Rio+20 conference, has the central role in overseeing a network of follow-up and review processes at the global level.

The 17 SDGs and 169 targets represent a much broader agenda than the MDGs, not only because of the increased number of goals and targets, but most importantly because the 2030 Agenda is universal, integrated, transformative, and grounded in human rights, governance, justice, and equity. The 2030 Agenda sets out a vision of a world free of poverty, hunger, disease, discrimination, fear, and violence; with equitable access to quality education and healthcare, with universal respect for human rights and human dignity, the rule of law, justice, equality and where people live in harmony with nature.

The magnitude of financial resources, technology transfer, and capacity building required to bring about this ambitious vision is unprecedented. This is why the Addis Ababa Action Agenda is critical to achieving the SDGs. The AAAA contains a global framework for financing development, which includes the use of domestic public resources, private business and finance, international development cooperation, international trade, debt and debt sustainability, science, technology, innovation, and capacity-building. The AAAA and the 2030 Agenda jointly established a “Technology Facilitation Mechanism” (TFM) to support SDG implementation through multi-stakeholder collaboration and partnerships, and the sharing of information, experiences, best practices, and policy advice.

The Paris Agreement is also integral to the 2030 Agenda, given the many ways climate change harms economic development as well as human and environmental health. SDG 13 (climate change) left action to the UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement’s goal is to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels. To this end, countries are required to submit plans for climate change action known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Without the necessary actions to reduce greenhouse emissions, the world is unlikely to achieve the 2030 Agenda.

COVID-19 Challenges and Opportunities

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, governments were making uneven progress on the SDGs. The world was off track to end poverty by 2030, food insecurity was on the rise, inequality was increasing, and the environment was deteriorating (United Nations, 2020). But COVID-19 has reversed years of progress on poverty, hunger, gender equality, healthcare, and education. While the virus has impacted everyone, it is harming the world’s poorest and vulnerable the most. It has exposed and exacerbated existing inequalities and injustices.

Women and children have borne the brunt of the crisis. Many women face increased economic insecurity and have taken on additional care work due to the closure of schools and day-care centres. Lockdowns increased the risk of violence against women and girls. Disrupted healthcare and limited access to food and nutrition services may result in hundreds of thousands of deaths of children under five and tens of thousands of maternal deaths. Around 370 million children missed out on school meals due to school closures and 70 countries reported disruptions or a total suspension of childhood vaccination services. As more families fall into extreme poverty, children are at much greater risk of child labour, child marriage, and child trafficking. In fact, the global gains in reducing child labour are likely to be reversed for the first time in twenty years (UN/DESA, 2020).

The world has seen many crises over the past 30 years, including the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–09. Each has hit human development hard but, overall, development gains accrued globally year-on-year. COVID-19, with its triple hit to health, education, and income, may change this trend.

At first glance, the COVID-19 pandemic poses an insurmountable obstacle to achieving the 2030 Agenda. In reality, the only way out of the crisis is through its application. The SDGs and the 2030 Agenda are well suited to act as a roadmap to coordinate global responses to a crisis with the scale, depth, and complexity of this unprecedented pandemic. The continued pursuit of these goals will keep governments focused on what is needed for recovery: inclusion, equity, growth, resiliency, and sustainability. While focusing resources on the specific targets included in SDG 3 (Good health and well-being) would directly address the health impacts of COVID-19 and build global resilience for future pandemics, concerted efforts to achieve goals on reduced inequality, increased access to clean water and sanitation, and increased protection of ecological health would greatly reduce the potential of a future zoonotic disease outbreak growing into a devastating pandemic.

This is a clear indication the Agenda was accurate in its original multidimensional, integrated, and universal vision grounded in equity, inclusiveness, resilience, and justice. It provides a global roadmap for recovery, recognizing the complex links between issues as well as the risks to all human well-being when even one person is left vulnerable.

Eradicating poverty, combating climate change, and recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic are defining challenges of our time. They test the international community’s resolve to drive forward the 2030 Agenda to achieve the SDGs. These challenges require increased solidarity, bold multilateral action, and strengthened partnerships to “build back better” by creating more sustainable, resilient, and inclusive societies (UN, 2020). Partnerships among governments, civil society, the private sector, foundations, and non-governmental organizations have emerged as an essential paradigm in sustainable development and key to achieving the SDGs.

But for this to happen, said UN Secretary-General Guterres at the annual ECOSOC high-level segment in 2020, focused and targeted action needs to be directed to the vulnerabilities and inequalities within and among countries that the COVID-19 crisis has revealed and exacerbated.

The MDGs taught us “what gets measured gets done” because many countries were able to integrate these measurable goals into their development plans and budgets (UN, 2015, p.10). However, there is still a need for countries to collect and disaggregate data from which to understand progress towards these critical goals. This disaggregation, for example, could include breaking data down by gender and age. Data based on national averages misses the opportunities to identify specific challenges that must be addressed if we are to fully implement the 2030 Agenda (Bizikova, 2017).

The 2030 Agenda pledges to “leave no one behind” and recognizes that the pursuit of sustainable development can only be rooted in respect for human rights, equity, and justice. Governments and businesses should heed the lessons learned from this COVID-19 “wake-up call” to transition to and build a healthier, more resilient, and more sustainable world. Central to this transition are timely and disaggregated data and statistics, from which effective and equitable measures and policies can be shaped (UN, 2020, p.3). We must now target our actions to those areas most in need of attention to effectively advance the 2030 Agenda and transform our world.

Works Consulted

Bizikova, L. (2017). Disaggregated Data is Essential to Leave No One Behind. IISD. https://www.iisd.org/articles/disaggregated-data-essential-leave-no-one-behind

Chasek, P.S., Wagner, L.M, Leone, F., Lebada, A., & Risse, N. (2016). Getting to 2030: Negotiating the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda. Review of European Community and International Environmental Law 25(1), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.12149

Dodds, F., Donoghue, D., & Leiva-Roesch, J. (2016). Negotiating the Sustainable Development Agenda: A Transformational Agenda for an Insecure World. Routledge.

Dodds, F., Laguna-Celis, J., Thompson, E. (2014). From Rio+20 to a New Development Agenda: Building a Bridge to a Sustainable Future. Routledge.

Dodds, F., Strauss, M., & Strong, M. (2012). Only One Earth: The Long Road via Rio to Sustainable Development. Earthscan.

Hulme, D. (2007). The Making of the Millennium Development Goals: Human Development Meets Results-based Management in an Imperfect World, Brooks World Poverty Institute Working Paper 16.

Kamau, M., Chasek, P., & O’Connor, D. (2018). Transforming Multilateral Diplomacy, The Inside Story of the Sustainable Development Goals. Routledge.

Tran, M. (2012). Mark Malloch-Brown: developing the MDGs was a bit like nuclear fusion. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2012/nov/16/mark-malloch-brown-mdgs-nuclear

UNDP/World Bank. (2016). Transitioning from the MDGs to the SDGs. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/sustainable-development-goals/transitioning-from-the-mdgs-to-the-sdgs.html

UN. (2015). Millennium Development Goals Report 2015. https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf

UN. (2020). Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2020.pdf

UN/DESA. (2020). Policy Brief #81: Impact of COVID-19 on SDG progress: A statistical perspective. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-81-impact-of-covid-19-on-sdg-progress-a-statistical-perspective/

UN General Assembly. (2001). Road map towards the implementation of the United Nations Millennium Declaration. A/56/326. https://undocs.org/A/56/326

You might also be interested in

Web of resilience

Pakistan's development model has still not recognised the limits of the natural environment and the damage it would cause, if violated, to the sustainability of development and to the health and well-being of its population. Pakistan’s environment journey began with Stockholm Declaration in 1972. A delegation led by Nusrat Bhutto represented the country at the Stockholm meeting, resulting in the establishment of the Urban Affairs Division (UAD), the precursor of today’s Ministry of Climate Change. In setting the country’s environmental agenda, we were inspired by the Stockholm Principles, but in reality, we have mostly ignored them for the last five decades.

Global Dialogue on Border Carbon Adjustments: The case of Brazil

This report consolidates, analyzes, and presents the views and perspectives of stakeholders from Brazil on border carbon adjustment (BCA) schemes to contribute to the global debate on BCA good practices.

Border Carbon Adjustments: Trinidad and Tobago country report

This report consolidates, analyzes, and presents views and perspectives of stakeholders from Trinidad and Tobago on border carbon adjustment (BCA) schemes to contribute to the global debate on BCA good practices.

A Balancing Act

With Nigeria's growing population in need of wide-ranging solutions to the multidimensional poverty it faces, a new IISD report outlines how the LNG dash could ultimately leave the economy more vulnerable to external shocks and without a solid domestic foundation.