Revisiting Tax Incentives as an Investment Promotion Tool

Introduction

In January 2024, a new system of international tax rules—the global minimum tax—will come into effect. These rules will impact the continued utility of some tax incentives as investment promotion tools by ensuring that large multinational companies pay a minimum effective tax rate of at least 15% no matter where they operate.

The effectiveness of tax incentives as an investment promotion tool has, however, been in question since the early 2000s, with some institutions that once championed their use calling for more cautionary application. Governments have, nonetheless, continued to extend tax incentives to investors, sometimes shortening their duration or imposing performance requirements on investors in efforts to ensure more direct benefits.

The stricter governance of tax incentives is indeed one way to minimize the unnecessary revenue losses that they may result in. However, it is important for governments to rethink their broader policies surrounding investment promotion and the use of tax incentives, reconciling these with changes in the broader investment landscape, including emerging international taxation rules, changing global value chains, and shifts to more sustainable production processes.

Recently, the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) published a Q&A intended to update the investment community on the evolution of tax incentives as an investment promotion tool. It revisits the foundational premises surrounding the use of tax incentives and builds on an earlier policy brief titled Rethinking Tax Incentives, as well as IISD’s more recent work on the interaction between tax incentives and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]/G20 global minimum tax. This brief will highlight the five core questions posed in the Q&A.

How do tax incentives differ from other investment incentives?

Tax incentives are fiscal terms designed to reduce the cost of investment by lowering an investor’s tax liability. They have direct and quantifiable monetary benefits for investors. They can be divided into two broad categories based on their nature, namely profit-based and cost-based incentives.

- Profit-based tax incentives reduce the amount of tax payable by an investor—for example, by granting investors tax holidays or reducing the applicable tax rate.

- Cost-based tax incentives defer the payment of tax due to the government through, for example, the extension of extended loss carry-forward periods or accelerated depreciation.

Tax incentives are, however, not the only investment promotion tool at the disposal of governments. Non-tax incentives are measures put in place to make it easier for investors to do business in a specific jurisdiction or provide investors with financial support to carry out their business. They are commonly known as investment facilitation measures and can include making administrative procedures more effective and efficient or using cash grants and subsidies.

Are tax incentives an effective investment promotion tool?

It is difficult to answer this question definitively because to do so would require a determination of whether specific investments would have taken place in the absence of an incentive. This challenge is further complicated by the fact that tax incentives are often introduced in conjunction with other ease-of-doing-business reforms, which may exaggerate the impact of tax incentives on investment decisions. Various empirical studies, including the 2015 Report to the G-20 by the Platform for Collaboration on Tax, have, however, found that most investments would have taken place even in the absence of a tax incentive.

Even where an investment has been enabled by the provision of an incentive, the effectiveness of tax incentives has been found to vary depending on the type of investment and the sector it is in. Investment in primary sectors, such as agriculture and mining, has largely not been driven by tax incentives, ostensibly due to the location-specific sector of these investments. Investments that depend on agglomeration effects and investments in local markets that are less mobile in nature are less responsive to incentives. Although these broad categorizations are now significantly better understood, there remains a need for fine-grained research on how different types of incentives impact sectors differently.

Tax policy and the specific use of incentives are, however, only one factor that investors consider when making investment decisions. Investors are concerned about a country’s overall investment climate, including political and macroeconomic stability, the availability of a skilled labour force, the ease of repatriation of funds, and many other factors. The importance of tax settings should thus not be overemphasized. Tax settings alone cannot compensate an investor for an overall unfavourable investment climate that will make it difficult for them to conduct their business. In fact, tax incentives can withhold government revenues that could be used to improve investment-related infrastructure.

How will the global minimum tax impact the continued use of tax incentives?

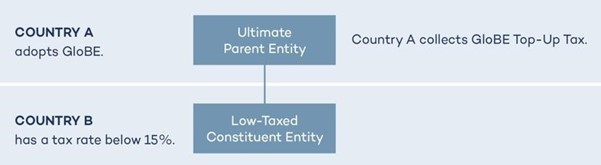

In 2021, 137 members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework agreed to a two-pillar solution to address tax base erosion and profit shifting by multinationals. Pillar 2 of this proposal establishes a global minimum tax of 15% that will apply to all multinational companies with an annual turnover of EUR 750 million or more. The aim of this initiative is to curb the proliferation of harmful tax competition that has led to the so-called “race to the bottom.” Under these rules, the tax benefit that a multinational receives in one jurisdiction will remain payable in another implementing jurisdiction, to the extent that the tax benefit reduces the effective tax rate of that multinational below 15%. Figure 1 presents a simple illustration of the global minimum tax’s primary rule.

Figure 1. The basic operation of the income inclusion rule under the Global Anti-Base Erosion System

Source: IISD-ISLP Guide.

Source: IISD-ISLP Guide.

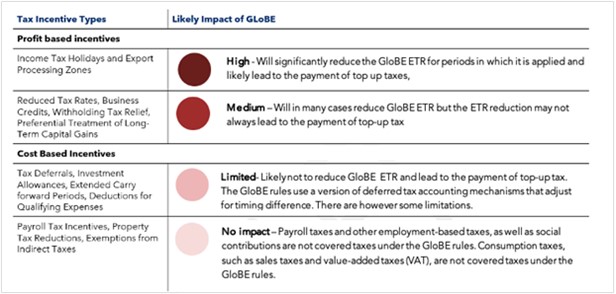

In order to retain primary taxing rights and to ensure that no other country has a right to collect revenue made within its jurisdiction, countries should consider unwinding the most harmful types of tax incentives, which are broadly profit-based tax incentives. Table 1 provides a categorization of the types of tax incentives most likely to result in revenue losses under the global minimum tax regime.

Table 1. Impact of the global minimum tax on types of tax incentives

Source IISD-ISLP Guide.

Factors to keep in mind when unwinding tax incentive regimes

Tax incentive reform can be a long and daunting exercise, which could explain why many ineffective incentive regimes persist. This is because tax incentives do not exist in vacuums. They are often embedded and reinforced in several domestic and international legal sources, including corporate income laws, investment laws, bilateral and regional treaties, and trade agreements. To coherently unwind a tax incentive regime, a government will need to establish where and how to make the necessary changes. This includes first mapping out all the sources of incentives and then investigating any barriers to reform, most notably the potential impact of legal guarantees of fiscal stabilization, which is addressed in the Q&A. The overall benefits of conducting such a review far outweigh the risks of sustaining an ineffective tax incentive regime.

What is the future of tax incentives?

It is not the intention of the global minimum tax to bring an end to the use of all tax incentives. The rules target only the most harmful types of tax incentives, which are broadly profit-based incentives. Developing countries will most likely continue to use tax incentives as an investment promotion tool for the foreseeable future. These incentives must, however, be designed and administered in a sustainable and responsible manner. Specifically, governments should

- ensure that any use of tax incentives is underpinned by sound economic rationale. Companies requesting tax incentives should for example be mandated to prove the commercial need for an incentive through financial models that simulate the investment circumstances, including the impact of incentives on investor returns and government revenues.

- make use of targeted incentives that have been proven to stimulate investment in specific sectors, limiting their reliance on profit-based incentives that are more susceptible to abuse but also less effective at encouraging investment in comparison to cost-based incentives.

- monitor incentives carefully to measure if they are achieving their intended results, discarding those that do not perform.

- foster transparency and inter-agency coordination, which will be critical to the effective administration of tax incentives. Ensuring accountability in the way incentives are granted and monitored significantly reduces opportunities for rent-seeking and corruption.

The continued use of incentives should be carefully considered in light of global changes that are altering investment patterns beyond the global minimum tax. Countries may, in some sectors, be better served by investing in other determinants of capital location decisions, including physical infrastructure, human capital, and the rule of law.

Conclusion

Countries that continue to use tax incentives as an investment promotion tool should be aware of the increased revenue loss risks that these fiscal tools will pose in light of the global minimum tax. The IISD Q&A aims to aid investment practitioners consolidate the wealth of knowledge on the utility of tax incentives so as to help them reconsider their continued effectiveness within their jurisdictions. It builds on previous IISD knowledge products on the impact of the global minimum tax on investment tax incentives including a blog article, an insights piece, and a Guide for Developing Countries on How to Understand and Adapt to the Global Minimum Tax. The recently established IISD Centre on Tax Incentives and Sustainable Investment has begun offering technical assistance to countries embarking on review processes of their use of tax incentives both in light of the global minimum tax and more broadly. Countries are welcome to channel requests of this nature to either the IISD Investment or tax teams.

Authors

Kudzai Mataba is a Policy Analyst at IISD, Investment and Tax.

Alexandra Readhead is the Lead of Tax and Extractives at IISD.