Why Canada Is Unlikely to Sell the Last Barrel of Oil

The Bottom Line: Unpacking the future of Canada's oil & gas

Re-Energizing Canada is a multi-year IISD research project envisioning Canada's future beyond oil and gas. This policy brief is part five of The Bottom Line series, which digs into the complex questions that will shape Canada's place in future energy markets. (Download PDF)

Summary

- Canadian producers are vulnerable to two foreseeable threats: declining global demand for oil and falling oil prices.

- Almost all Canadian exports go to U.S. refineries. This reliance on captive buyers will initially shield Canada from the worst of the decline in demand, but this buffer will not last.

- Nothing will shield Canada from global oil price drops and volatility. Pressure on Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries-plus discipline as members rush to increase oil production in the face of declining demand will result in prices that are low and even more volatile than normal.

- Canadian oil producers’ environmental, social, and governance performance will not help preserve Canada’s market share, since it does not matter to the refineries buying the product.

- Marginal producers will not survive in the post-peak market, and efficient producers will see low profits, remitting low royalties and taxes. In line with history, large numbers of workers will lose their jobs in the sector.

- Canada cannot afford to delay support for diversifying into sectors that can replace oil as an engine of economic prosperity.

Oil demand and oil prices are currently booming, spurred by under-investment in exploration and an unexpected demand surge as COVID-19 restrictions were lifted, and greatly exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Nonetheless, almost all analysts see global demand for oil peaking around 2030 (BP, 2022; DNV, 2022; International Energy Agency [IEA], 2022; McKinsey, 2022; Rystad Energy, 2022). Recent International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) analysis predicts falling demand by 2030 and significant declines thereafter as new technologies and ambitious climate policies eat into all of oil’s major end uses.

It is not obvious, though, what that means for Canadian oil producers. Will they thrive even as the global market shrinks? Will Canadian environmental, social, and governance (ESG) credentials help grow or maintain the country’s market share? Will they, as suggested by former Premier of Alberta Jason Kenney, help Canada buck global circumstances and sell the proverbial last barrel of oil?

This policy brief explores four factors that define the answers to those questions:

- The destination of Canada’s crude oil exports

- Whether Canada can win markets with its ESG credentials

- Whether Canada can win markets on price

- What to expect from Canada’s global competitors

Almost All of Canada’s Oil Exports Go to U.S. Refiners

In 2021, Canada exported 3.3 million barrels per day (bpd) of crude oil, or 80% of domestic production (Canada Energy Regulator, 2022; UN Comtrade, 2021). Over 94% of those exports went to the United States, and 80% were in the form of heavy crude of the type produced in Western Canada’s oil sands.

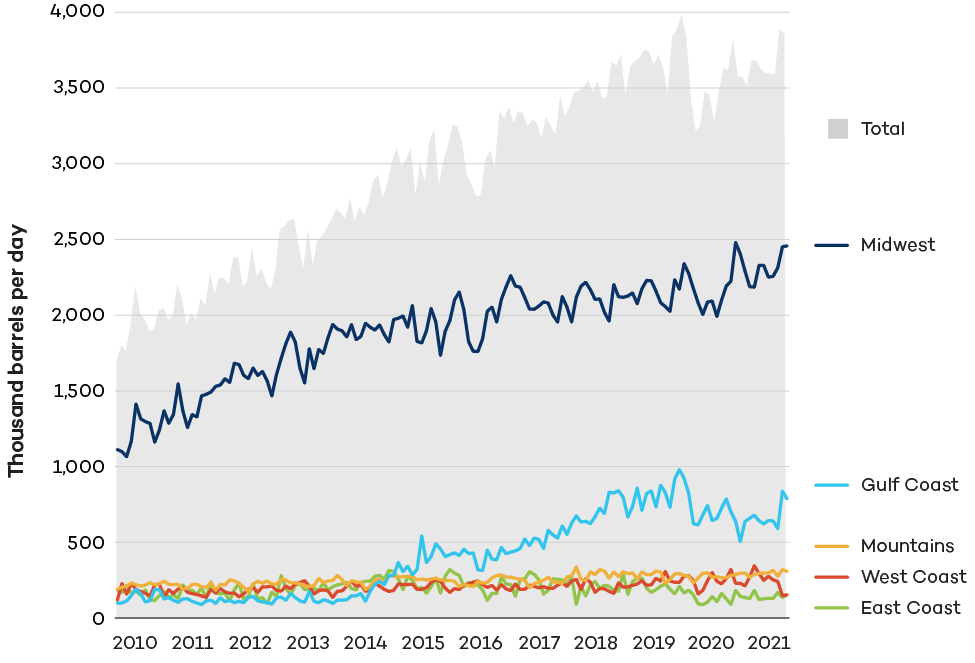

Figure 1 shows where those exports went: overwhelmingly to Midwest refiners in Illinois and Minnesota (primarily through the Enbridge and Keystone pipeline systems), but increasingly also to Gulf Coast refiners as U.S. pipeline reversals and transport by rail have increased Canadian producers’ ability to reach them.

Figure 1. U.S. refining district destinations for Canadian crude exports

Several major Midwest refineries and some Gulf Coast refineries are deliberately set up to refine oil sands-type heavy crude. Many in the Midwest have made recent multibillion-dollar investments in capacity specifically designed to do so. For the Midwest refineries, Canada is the only viable source of crude feedstock; they do not have tidewater access to import crude from other suppliers (or to export their final product). Gulf Coast refiners can import crude by tanker, but other global sources of heavy crude—primarily in Mexico and Venezuela—have dropped to almost negligible levels of production, so Canada is a critically important source.

What will those export patterns mean for Canada when global demand drops? Canadian oil exporters are potentially vulnerable to two forces: lower demand and lower price. On demand, Canada is partially insulated from global trends because it mostly sells to Midwest U.S. refiners whose output is consumed in the United States. But Canada is not completely insulated from drops in global demand for three reasons:

- U.S. demand itself will be dropping. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act is projected to shave 2.1 million bpd off U.S. demand for petroleum products by 2030 and 4.1 million bpd by 2035, relative to 2021 U.S. consumption of 18.6 million bpd of crude. Those numbers are likely underestimates since they do not factor in the ban on the sale of conventional light cars and trucks in California by 2035 or the follow-on announcements that will come from 15 other states with linked regulatory regimes.

- Though U.S. demand decreases won’t necessarily translate directly into reduced Canadian imports (the complex modern refineries to which Canada sells would not likely be the first to cut production), the pressure for such cuts will be significant. U.S. refiners exported 46% of their production in 2021, and they will be selling into a declining global market.

- A small but increasing amount of Canadian crude finds its way to markets beyond the United States through the Gulf Coast in flows that reached almost 300,000 bpd in 2021. The expansion of the Transmountain pipeline to the Canadian West Coast would, if completed, add another 600,000 bpd of non-U.S. export capacity. Combined, that would amount to 27% of total 2021 exports.

The conclusion is that Canada’s U.S. export patterns provide a buffer but do not shield it much from lower demand for its exported crude oil as global demand drops.

Canada is also directly vulnerable to the price impacts of a global decrease in demand, and its U.S. export markets do little to shield it from those impacts. Prices are, to a large extent, set in a global market. Those prices are set both by demand and supply, however, so it matters what Canada’s global competitors will do as demand falls—a topic that is explored below.

ESG Credentials Will Not Preserve Canadian Oil’s Market Share

If Canada were vying to sell the proverbial last barrel of oil, would it matter how its oil was produced? Would greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity matter, for example, or would it matter whether it was considered “ethical” or produced to high ESG standards? The short answer is: probably not.

For some products, production methods impact marketability. At comparable price and quality, final consumers will favour “green” and ethically produced products. For goods like food, clothing, and electronics, a variety of labelling schemes allow consumers to choose, even to pay a premium for labelled products. But for commodities like oil, the situation is different. When refined Canadian oil is finally sold at the pumps, it is indistinguishable from other gasoline, and tracking the source at the retail level would be daunting. The original customers are mostly U.S. refiners dependent on the supply of heavy Canadian crude, as detailed above, who focus on quantity, quality, and price—not ESG. ESG considerations clearly matter a great deal to oil sector investors (Flavelle, 2020; Graney, 2021), but they do not preoccupy most customers. While investors influence companies’ ability to finance expansion, new projects, and infrastructure, they don’t buy the final product, and therefore their opinions don’t directly affect a company’s market share. This will be especially true in the context of a shrinking market in which Canadian producers will not need to expand operations to compete for the few remaining buyers. Canadian crude oil’s emissions intensity would matter if the United States implemented a clean fuel standard governing the life-cycle carbon content of transportation fuels such as gasoline. By design, such a standard would reduce the market share of crude oil produced at high emissions intensity, including most of Canada’s U.S. exports (see Box A). California, Oregon, and Washington have clean fuel standards in place. But, while such a policy has been suggested by legislators (House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, 2020; Senate Democrats Special Committee on the Climate Crisis, 2020), it would face strong opposition from the domestic refining sector and raise the price of gasoline for American drivers, making it unlikely to pass in the foreseeable future.

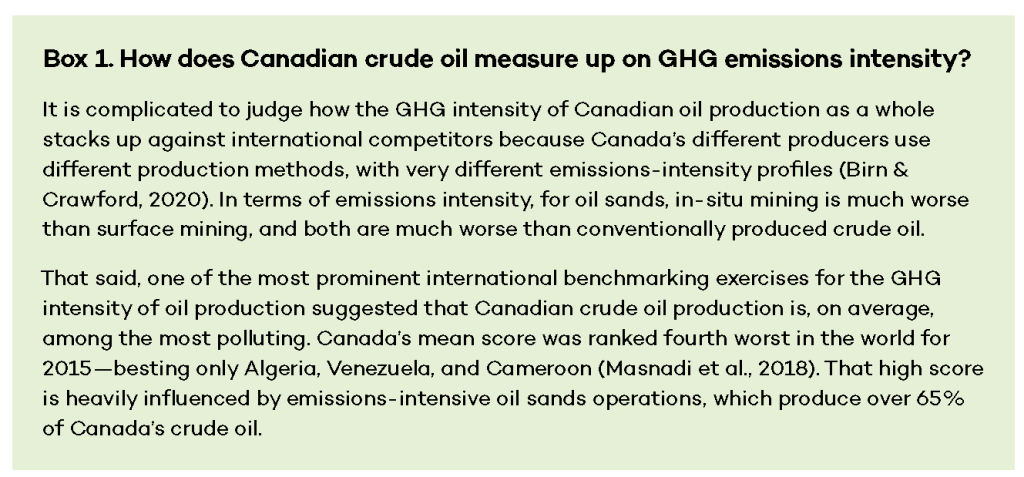

Beyond the question of whether ESG matters for Canadian oil’s market share is the more basic matter of whether Canada’s producers are, in fact, world leaders on ESG criteria, as claimed by some industry groups and pundits (Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, n.d.; Dziuba et al., 2020).

On environmental performance, the section above makes it clear that Canada’s overall GHG intensity of production is not world class. Beyond emissions, Canada’s oil sands operations have been dogged for years by a record of serious water and air pollution impacts (Alberta Environmental Monitoring Panel, 2011; Leahy, 2019; Liggio et al., 2016). Those impacts were singled out as disproportionately affecting Indigenous peoples by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes.

Oil sands development has been responsible for extensive impacts on the traditional territories of many First Nations in Alberta, in violation of treaty rights and without proper consultation or respect for basic principles such as cumulative effects management. In many instances, the industry’s consultations and impact assessments with respect to Cree, Dene, and Métis rights have been designed in a manner to expedite oil sands development. Members of many Nations in the region, such as Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation and Fort McKay First Nation, have denounced these impacts for decades. Additionally, the Beaver Lake Cree Nation has an ongoing lawsuit against the governments of Alberta and Canada on the basis that the cumulative impacts of this industrial development violate their Treaty 6 rights.

While ESG matters to investors and to builders of pipelines seeking social license, it does not matter to the refineries that buy Canada’s oil.

Canadian producers’ mismanagement of the end of the oil and gas project life cycle should also be considered. In Alberta, as of September 2022, 3,309 oil and gas sites are considered orphaned, meaning the original owners failed to fulfill their responsibility for costly end-of-life decommissioning and restoration. Many of those sites were strategically sold to insolvent operators. Responsibility for them now falls to the industry-funded Orphan Well Association, but current industry contributions are grossly inadequate. The Association has CAD 169 million in assets against orphaned sites that it estimates will cost almost CAD 700 million to clean up. Liability estimates for all existing sites are much higher, reaching up to CAD 260 billion. The difference has partly been borne by taxpayers through government loans and bailouts to treat inactive and orphaned wells, violating the polluter-pays principle. But most orphan wells remain unremediated, and a large proportion of “active” wells are, in fact, inactive but not declared as such, meaning the farmers and ranchers on whose land they sit suffer the environmental and economic consequences.

Similarly, it is arguably an ESG issue that some Alberta oil and gas companies owe hundreds of millions of dollars in unpaid municipal taxes and tens of millions of dollars in unpaid lease payments to landowners.

Some insist the last barrel of oil should be sold by a country like Canada that respects democracy and human rights. However, this is largely beside the point: while Canada as a country may have better ESG institutions than many of the world’s top oil-producing countries, ESG criteria traditionally centre on the behaviour of the firm in question, not the government policies where they happen to operate. Some Canadian oil producers score well on ESG criteria, and others score poorly.

Ultimately, however, whether Canada’s producers’ ESG rating should preserve its market share is irrelevant. As argued above, it won’t; buyers of Canadian oil don’t discriminate on ESG grounds.

Canada Is Far From the Lowest-Cost Producer

If ESG status won’t save Canadian oil’s market share, could Canada compete on price? Most of Canada’s crude oil exports do not compete directly on global markets, though there are increasing exports from the U.S. Gulf Coast that do, and there will be substantially more with the completion of the TMX pipeline. And Canadian crude does not compete directly with the lighter, sweeter crude produced in most other countries. But Canada’s costs of production relative to its major competitors still matter in the long run, especially in a shrinking post-peak global market.

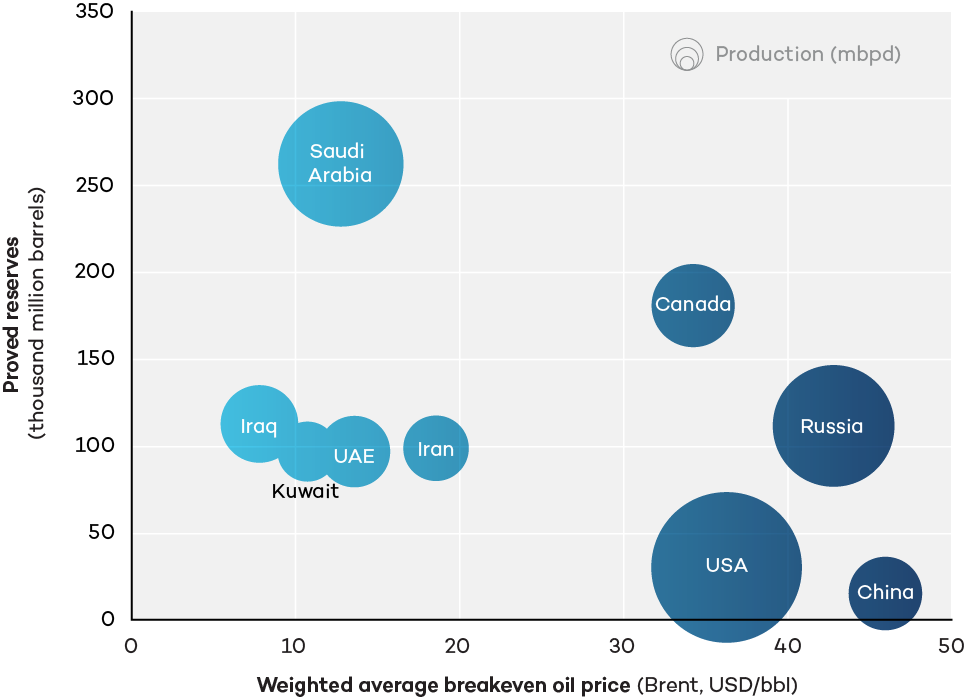

Figure 2 shows how those costs measure up among the top 10 oil-producing nations, expressed here as the weighted average Brent crude U.S. dollar per barrel breakeven price in each country. While costs of production have come down dramatically in Canada over the last 20 years, Canada is still not a low-cost oil producer, especially compared to its Middle Eastern competitors.

Figure 2. Global costs and reserves

Note: Horizontal axis is the weighted average breakeven oil price for all existing producers. Bubble size indicates 2020 production levels.

As of November 2022, the price of Brent crude is in the mid-eighties (USD), so prices could fall significantly before most Canadian producers, with a weighted average breakeven oil price of USD 35.21, became unprofitable. But in a future global market with falling demand and prices, there would be significant reserves and production in countries that would continue to be profitable long after Canadian production is not.

The Post-Peak Market for Oil Will Be Savage

Despite Canada not currently participating directly in global markets, global supply and demand trends—and the prices that result from them—directly affect the price Canadian oil producers receive. It is, therefore, important to forecast the strategic behaviour of non-Canadian producers in response to what we know is coming: a peak of global demand by around 2030, followed by a marked decline.

In the face of lower returns driven by climate policy, some have predicted a dynamic known as the green paradox, where producers predict their reserves will be worth less in the future, and rush to extract and sell more of them in the present. This would mean lower prices for all (and more consumption of cheap oil, hence the paradox). Others have criticized this theory, noting that significantly ramping up production is not a simple matter for most producers, particularly in the short term.

In today’s circumstances, however, the green paradox would not necessitate a difficult ramp-up—it could simply amount to deliberately following existing plans in the face of declining demand. A survey of production plans for 12 major oil-producing countries shows projected increases by 2030 amounting to more than 10% of 2020 global production. By contrast, under plausible assumptions, global demand for oil could decline 22% by 2030 and more steeply thereafter.

International (private) oil companies might change expansion plans in response to obvious decline trends; some shareholders would likely demand it. In the same vein, Cairns (2014) also criticizes the green paradox model on the grounds that it would be economically irrational for major producers to increase production and tank prices. But more than half of global oil supply comes from national oil companies. These companies are not strictly profit motivated, and are usually mandated by national governments to contribute to broader policy objectives, such as creating employment. Some national governments will very likely demand a ramping-up of production in the face of declining demand and prices.

For decades, global oil markets have been protected from oversupply by the discipline of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and, more recently, OPEC-plus. But the organization has always been subject to tensions, with heavily oil-dependent members seeking to increase production to address their urgent development needs (Blas et al., 2020; Lee, 2020; Smith et al., 2020). Declining oil prices with no long-term prospect for price recovery would ratchet those tensions up to new levels, risking a loss of collective discipline and resulting oversupply and volatility.

All things considered, it is straightforward to predict whether Canada will sell the last barrel of oil; it will not.

Conclusions

How will the coming peak and drop in global demand affect Canadian producers?

They will face low and volatile prices for oil. There is a mismatch between planned increases in production and potential decreases in consumption, which indicates prices will also go down. The weakening of OPEC discipline in a post-peak-oil world may also create increased price volatility, which has outsized impacts on investment, royalties, and other elements of the Alberta economy in particular.

And they will face declining demand for their products. Canada’s focus on the United States as a destination market means it will be partly sheltered from global demand effects—U.S. refiners will buy Canadian crude even as global demand falls. But they will face increasing pressure as export markets are curtailed and domestic consumption falls. The refineries that buy Canada’s oil are large, complex, and low cost and are likely to maintain markets for some time even as demand shrinks, but at some point, even they will curtail production.

Meanwhile, Canada cannot count on its producers’ (often questionable) ESG credentials to preserve market share. While ESG matters to investors and to builders of pipelines seeking social licence, it does not matter to the refineries that buy Canada’s oil; they are largely locked into Canadian heavy crude by massive investments in the capacity to use it as a feedstock.

Neither can Canada rely on a low cost of production to help its position. While Canadian producers have reduced costs significantly since 2014, their oil is, on average, still much more costly than that of all the major Middle Eastern producers, which have huge reserves and capacity. In a battle to sell the last barrel, Canadian oil producers face a cost disadvantage.

All things considered, it is straightforward to predict whether Canada will sell the last barrel of oil; it will not. But the more immediate and fundamental question is this: how will Canada fare in the savage post-2030 market of declining demand—a market characterized by low prices and even more volatility than the historical norm? Canada’s marginal producers will not survive; its more efficient producers will reap low profits, remitting low royalties and taxes. New investments will be almost unthinkable, other than incremental extensions of existing operations. Based on past experience, between cost-cutting and lack of new investment, the sector will shed large numbers of workers.

The coming peak and drop in global demand matters for Canadian producers—in the long run, it presents an existential threat. In the near-to-medium term it promises to take the vitality out of a sector that has historically contributed enormously to the Canadian and provincial economies.

These realities are acutely important for Canadian government policy. Canada cannot afford to delay support for diversifying into sectors that can replace oil as an engine of economic prosperity while simultaneously building a cleaner, healthier world.

A full list of references can be found here.

Re-Energizing Canada is a multi-year IISD research project envisioning Canada's future beyond oil and gas. This publication is part three of The Bottom Line policy brief series, which digs into the complex questions that will shape Canada's place in future energy markets.

You might also be interested in

Why Canada Needs to Plan for a Steep Decline in Global Oil Demand

This analysis demonstrates that Canada can expect global oil demand to permanently decline in the very near term, as electric vehicle uptake and other societal changes pick up speed.

Why Government Support for Decarbonizing Oil and Gas Is a Bad Investment

A close look at the value of government support for decarbonizing Canada's oil and gas sector finds that public dollars are spent more effectively on readily available and proven low-carbon technologies.

Why Canada’s Energy Security Hinges on Renewables

This deep dive into the evidence shows investing in clean, flexible, and reliable electricity grids is the best option to increase Canadians' energy security, particularly long-term affordability.

Why Canadian Liquefied Natural Gas Is Not the Answer for the European Union’s Short-Term Energy Needs

This investigation shows that Canadian LNG infrastructure would come too late to address Europe’s energy security needs and offer little benefit to Canada’s economy.