Le COVID-19 et l’équilibre des pouvoirs

Dans le contexte de cette crise, les réponses apportées par les gouvernements devraient-elles se soustraire aux impératifs de transparence, de redevabilité et de responsabilité ?

Half the world’s population is subject to varying degrees of lockdown in an attempt to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments have adopted measures aimed at limiting disruptions to the normal functioning of society and at mitigating the adverse consequences of COVID-19. Even though containment measures have been universally legitimized by health authorities, they nonetheless affect freedom of religion, freedom of trade and of movement, and sometimes fundamental judicial guarantees as well. Where should one draw the line between public health measures and individual rights?

Faced with an unprecedented crisis, should governments offer solutions that sidestep requirements of transparency, accountability, and responsibility? In Malawi, the High Court blocked the implementation of public lockdown measures on the grounds that the government had failed to show how the country’s poorest citizens would be protected in the fallout. This unprecedented decision contrasts with many places in the world where parliaments have yielded in the face of government action.

Crises are paradoxical times in the world of politics; they heighten the demands for effectiveness that are placed on those in power while simultaneously testing the strength of institutions.

Parliaments play a crucial role as guardians of the democratic process, democratic values, and fundamental freedoms. It is, therefore, critical that they continue to function throughout this crisis while striving to provide democratic controls and to guarantee a balance of powers when possible.

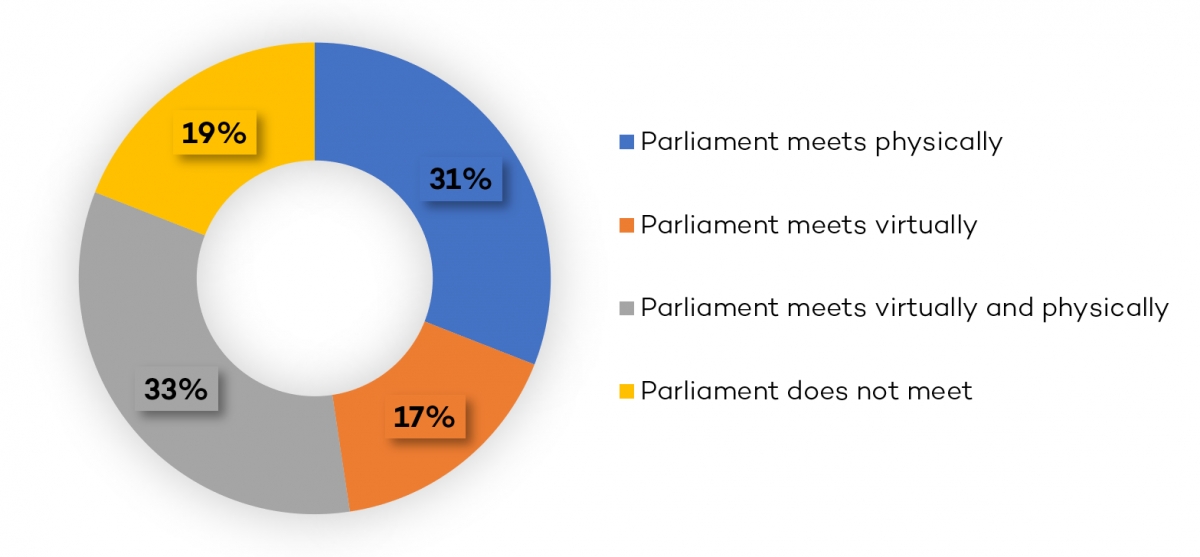

COVID-19 has raised unique challenges for parliaments’ capacity to continue their work. Due to social distancing and containment measures, nearly 20% of parliaments, including those of the United Kingdom, Myanmar, and China are currently not sitting, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). Others have adopted technological solutions to allow parliaments to meet virtually. Just over 30% of legislative assemblies have been able to maintain physical attendance, but with restrictions such as limitations on the number of parliamentarians allowed to attend plenary sessions and committees. In Senegal, 33 parliamentarians out of 165 voted for a bill empowering the President of the Republic to rule by executive decree on issues normally situated in the legal domain in order to respond to the pandemic. For a period of three months, the President is not required to go through the National Assembly to pass legislation on economic, budgetary, financial, legal, health, and security issues.

Source: How do Parliaments meet during Covid-19? Author diagram, based on testimonials gathered by the Inter-Parliamentary Union’s Centre for Innovation in Parliament in April 2020

In times of crisis, it is not unusual for the law to give way to other normative supports controlled by executive bodies. However, even if the circumstances of the pandemic warrant a declaration of a state of emergency or the granting of exceptional powers to the executive branch, this in no way should be construed as a blank cheque to the government—all the more so because emergency powers have a disturbing tendency to become permanent. There is a risk of resorting to a state of emergency that goes above and beyond its most basic purpose. The Hungarian Parliament has approved a law allowing its Prime Minister to govern by decree, with no end date. Some leaders have taken advantage of the coronavirus crisis to impose excessive restrictions on human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. If the state uses its power to the fullest extent, it risks becoming a dangerous Leviathan—hence the importance of measures to limit, control, and offset this power.

What Role Can Parliaments Play?

The power to control executive bodies whose prerogatives have been very widely extended to deal with the crisis is therefore paramount. Parliament is above all a supervisory body for the government and must remain so whether in normal times or in times of crisis. Parliamentarians must ensure that emergency measures are implemented correctly and according to democratic standards, that restrictions on freedoms are proportionate and provisional, that the use of armed force is justified and regulated, that economic support funds are paid out where they are needed, and that security and stability are maintained.

Parliaments can also participate in awareness-raising initiatives and promote transparency with regard to the health crisis, which is crucial for preserving the public’s confidence in government responses to the pandemic. Parliamentarians can interact with the public, imparting information and building awareness of the measures adopted by the executive. To this end, the parliamentarians of Sierra Leone are visiting their constituencies to raise people’s awareness of the dangers of the pandemic and to inform them about the precautionary measures they are advised to take.

COVID-19 has propelled the world into a very serious crisis. It is important that parliaments help design responses and support measures. Parliamentarians serve the central function of controlling the governmental response and also of evaluating and adopting emergency responsive legislation directing national funds toward meeting the needs of the population. More than ever, the citizens’ representatives must be present.

Working with new technologies, parliaments are already examining available solutions and the procedural options that will allow for new ways of debating and voting in their now-virtual environment. Collective deliberation remains the most reliable tool for ensuring balanced, fully developed legislation.

The medium- and long-term effects of the measures taken to slow and contain the spread of the disease remain unpredictable. Does safeguarding the democratic process and ensuring respect for the rule of law amount to questioning the balance of power between the government and the parliament? Yes—because otherwise, in times of crisis, what would the word “democracy” really mean?

You might also be interested in

National State of the Environment Report: Uzbekistan

The National State of the Environment Report (NSoER) is a comprehensive document that provides a snapshot of current environmental trends in Uzbekistan's socio-economic development for citizens, experts, and policy-makers in the country of Uzbekistan.

African Environmental Ministers Commit to Beyond GDP and Inclusive Wealth Measures

The 19th session of the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment showed increasing interest and commitment from African leaders to explore measures that go beyond GDP to gauge progress.

Policy Coherence and Food Systems Transformation

To develop national pathways toward sustainable food systems, we need to align a diverse range of policy areas. How can countries overcome contradictions, inconsistencies, and trade-offs?

Why was Africa exporting only about 1% of Soya, "The King Of Beans"?

Soy, often known as soja or soya bean, is the most popular plant-based protein source. It is also one of the most plentiful and inexpensive protein sources. Soya has become an essential part of daily life for people and animals in many parts of the world.