News August 17, 2021

This Is How You Turn Food Waste into Locally Grown Produce

By Paul Fafard, Field Sampling Technician, Dan Fafard, co-founder of the Harvest Kenora Collective

The field season at IISD Experimental Lakes Area is in full swing, and—in true IISD-ELA style—we’re trying something different; a new experiment, this time focusing on food-waste management!

This year, instead of sending our food waste to the landfill, we’ve teamed up with the Harvest Kenora Collective to put our waste to use and increase food resiliency in Kenora at the same time!

Much Ado About Bokashi

This season at IISD ELA, we are turning our food waste into “bokashi,” a high-quality garden amendment. The Harvest Kenora Collective is helping us toward sustainability by burying our bokashi in local gardens to boost soil quality and improve garden productivity —a win-win that helps us reduce our waste and allows us to contribute to a more sustainable and resilient local food system!

Bokashi is a term used to describe the process of using Lactobacillus spp. bacteria (the same bacteria used to make yogurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, and sour beer) to ferment food waste, preventing it from rotting and making it easy for soil organisms to break down. While the precise origins of the term are not clear, the fermentation of organic matter to use as a soil amendment goes back centuries in Korea and likely has its roots in Korean Natural Farming practices gaining popularity around the world.

This “Lacto-fermentation” process that occurs when making bokashi prevents decay by pickling food waste in an acidic, anaerobic environment. The Lactobacillus bacteria break down carbohydrates in the food waste and produce lactic acid, which staves off the “bad” bacteria and moulds while retaining the nutrients of the fermented materials. Bokashi is quickly broken down by the organisms in soil and provides a readily available source of nutrients for the plants, fungi, and other biota living there.

We began bokashi fermentation at our homes this past winter after listening to the October 31, 2020, episode of The Permaculture Podcast with Scott Mann. Bokashi has three main benefits over composting when it comes to food-waste management:

- Bokashi does not produce heat, CO2, or methane gas, all of which are or can be by-products of conventional composting. This means that bokashi provides more carbon to the soil ecosystem where it can be used by plants, rather than be emitted as a greenhouse gas.

- Bokashi fermentation can occur in a small space (e.g., a 20-litre pail) and is a process that occurs quickly at room temperature—as such, it can be done indoors during the winter months, unlike composting.

- Bokashi fermentation works on all food waste, including meat, bones, and dairy. It also works well on paper napkins, popsicle sticks, coffee filters and the like, cutting waste to zero!

Bokashi fermentation is also a low-odour process, especially during fermentation when the lid is on the bucket. The fermented bokashi and liquid do have a sour smell to them; however, this smell disappears quickly when the bokashi is buried in soil. The low-odour nature of bokashi fermentation is a major benefit that makes bokashi ideal for use at the IISD ELA field station: past attempts at food waste management through composting quickly caught the attention of the local black bear population, and no one wants to have to sprint from building to building to avoid encountering a hungry and curious bear (especially at night!).

How We Make the Magic Happen

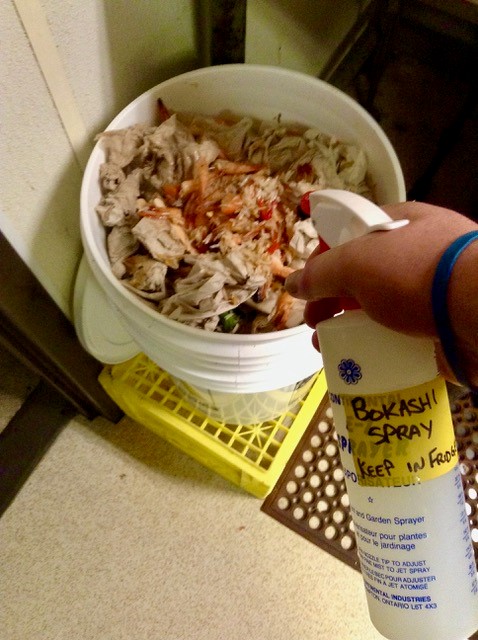

Making bokashi is pretty straightforward and can be done by anyone for managing their food waste at home—we’ve included steps at the end for reference. The key to bokashi lies in the Lactobacillus culture that is used to ferment the food waste. You can make this yourself (see steps at end) or purchase premade Lactobacillus inoculated bran that is sprinkled on food waste rather than sprayed. I found that keeping the bokashi spray in a bottle in the fridge was the simplest and most effective means of handling the quantity of food waste generated by 30 plus people in camp, as a little goes a long way.

At IISD-ELA, the bokashi process is simple enough for everyone to get the hang of quickly. Here’s a snapshot of what we are doing from plate to garden:

Bokashi is yet another satisfying step towards sustainability for IISD-ELA, and we are thrilled to be building a relationship with the Harvest Kenora Collective. With only a small amount of work, IISD ELA can make use of our food waste to create a high-quality garden amendment, and the Harvest Kenora Collective can use that bokashi to improve local garden soil and grow more food! Perhaps one day we can localize our food supply chain and close the loop entirely with produce grown by the Harvest Kenora Collective!

The IISD-ELA field station, as well as the Harvest Kenora Collective and the Homerun Gardens operate in Treaty #3 territory, on the traditional land of the Anishinaabe Nation and the homelands of the Metis people. Together, we are reducing our impacts on the land and working towards a more sustainable future.

How You Can Use Bokashi Fermentation at Home … or the Office!

- Make a Lactobacillus culture (optional: can also purchase ready-made bokashi bran online)

- This is a simple process and takes about one week. Start by rinsing ~ 1 cup of rice in a bowl and setting the rinse water out on the counter for two or three days, uncovered. The starch washed off the rice provides food for Lactobacillus spp. bacteria floating in the air (they are everywhere) and will allow them to greatly increase their population as they colonize the rinse water.

- In a large jar (1.6 litre or 4 litre works well), add the colonized rice rinse water 1:10 with milk (e.g., 100 millilitres of rice rinse to 1 litre of milk). Any unspoiled milk will do—I have used half-and-half that was a few days past its expiry but hadn’t curdled yet, with great success.

- Let the jar sit on the counter, covered with a cloth or paper towel, until the milk separates into a dense mass of milk solids and whey. This usually happens within 4 to 5 days.

- Strain the whey into a separate jar (through a thin tea towel works well). This is the Lactobacillus spp. culture that will be used to create bokashi! This liquid can be kept in the refrigerator for months, or if you add an equal weight of brown sugar to it, in a cool dark place for over a year. Fill a spray bottle with the Lactobacillus spp. culture so you can give your food waste a good spray whenever you add it to the bokashi bucket.

- The solids left over from the culturing process are essentially cheese and can be added to your food waste in the bokashi bucket or even eaten in a lasagna if you are feeling adventurous!

- Create a bokashi bucket (or two or three … or 12!)

- At IISD ELA, we use bokashi buckets consisting of two stacked 20-litre pails and a lid.

- Holes are drilled in the bottom of the inside (i.e., top) bucket, where food waste is deposited. The outside (i.e., bottom) bucket is left intact and the lid seals things up.

- The holes in the inside bucket allow liquid to drain out of the bokashi as it ferments.

- Ferment your food waste

- Put a layer of paper towel or tissue down on the bottom of the inside bucket to prevent coffee grounds or small bits of food waste from falling through the holes.

- Spray the bottom layer, and any food scraps you add to the bucket, with Lactobacillus spp. culture.

- Minimize air pockets by compressing the food waste in the bucket as you add it.

- Once the bucket is packed full, put the lid on and set it aside for a week or more to ferment. Fermentation is usually complete within 2 weeks.

- Drain the liquid from the bucket if it begins to saturate the bokashi from below

- Bokashi liquid can be used as a fertilizer if diluted 1:100 or 1:200 (e.g. 10 millilitres bokashi liquid into 1 or 2 litres of water).

- I usually just add this liquid to the garden soil whenever things are getting watered.

- Dig your bokashi into the garden once fermentation is complete

- It is essential that soil organisms and microbes have time to consume the bokashi to complete the process. Allow the bokashi a week or two in the soil before transplanting seedlings in the same spot.

Originating out of Climate Action Kenora, a group of climate concerned citizens, the volunteer group Harvest Kenora formed to address food security in Kenora. Having established the collective micro-farm Homerun Gardens in 2019, Harvest Kenora evolved and grew to become the Harvest Kenora Collective, with the mission to collectively grow food, relationships, and lifelong skills for healthier, more resilient communities and ecosystems. Past initiatives include the Resiliency Garden Campaign (2020) where the Collective provided hundreds of volunteer-grown seedlings, regional seeds, container gardens, and local manure, along with gardening advice for participants to successfully grow their own food at home during the Pandemic. Through this initiative, the Collective supported novel and experienced gardeners alike to boost food resiliency in Kenora while nurturing relationships through growing food. This year, Homerun Gardens is once again open to everyone as a place to come and learn about, participate in, and build relationships around growing food in a sustainable way. As always, the produce is grown by—and for—the community. Please feel welcome to join the twice-weekly garden parties and enjoy the fruits of your labour with fresh, nutrient-rich produce picked straight from the garden.

Learn more, and consider supporting their work, at www.harvestkenora.ca