Advancing Green Public Procurement and Low-Carbon Procurement in Europe: Insights

In 2021, IISD began a collaboration with SKAO (funded by the IKEA Foundation) to scale up the uptake of the CO2 Performance Ladder in Europe. The goal of the project is to identify potential pilot projects in European countries in order to demonstrate the effectiveness of a tool that works towards advancing green public procurement and carbon reduction goals. The first step toward that goal was to carry out a "quick scan" of the GPP situation and the possibilities for the Ladder across 28 European countries through desk research. This resulted in a number of observations regarding GPP in the region.

Public procurement provides a key entry point for governments to change the trajectory of their greenhouse gas emissions and to meet climate goals in line with their international commitments to the Paris Agreement, the Sustainable Development Goals, and—in Europe—to the European Green Deal. In the coming years, it is essential for public procurement, which accounts for 15% of carbon emissions globally, to become a driver of innovation and commercialization of low-carbon infrastructure, goods, and services.

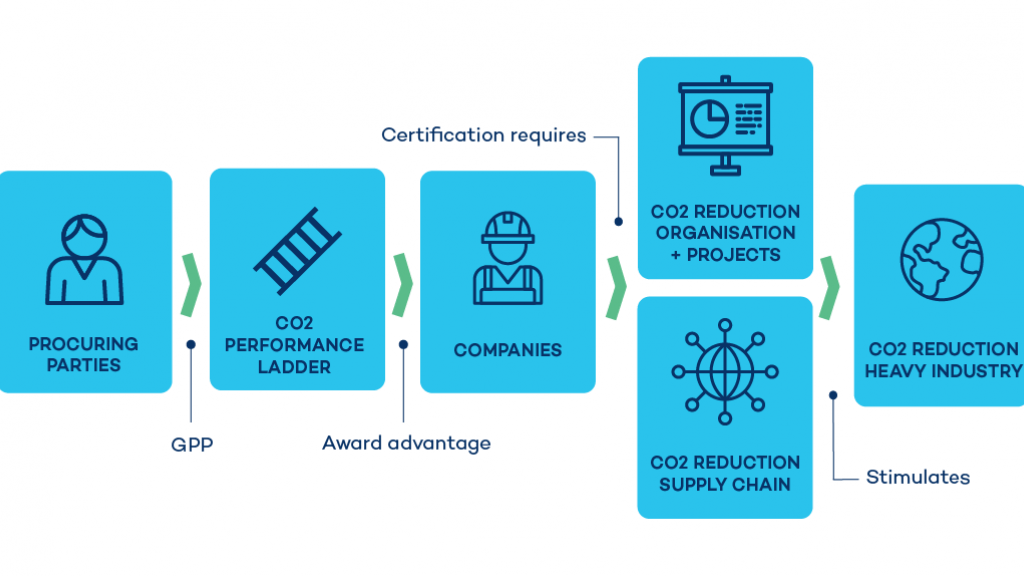

This is the challenge that the CO2 Performance Ladder was designed to address. Developed in the Netherlands in 2009 for the rail sector, it is now owned and managed by the Foundation for Climate Friendly Procurement and Business (SKAO). The CO2 Performance Ladder helps organizations structurally reduce their carbon emissions as both a CO2 management system and a procurement tool. Over 4,000 organizations are certified on the Ladder, and it has been used by over 200 public procurement agencies in the Netherlands and Belgium in their tendering processes.

The CO2 Performance Ladder offers the following advantages as a procurement tool:

• It is user friendly and has low transaction costs for getting started. Procuring authorities simply offer companies the option to submit a form along with their bid attesting to their proposed level of commitment on the Ladder.

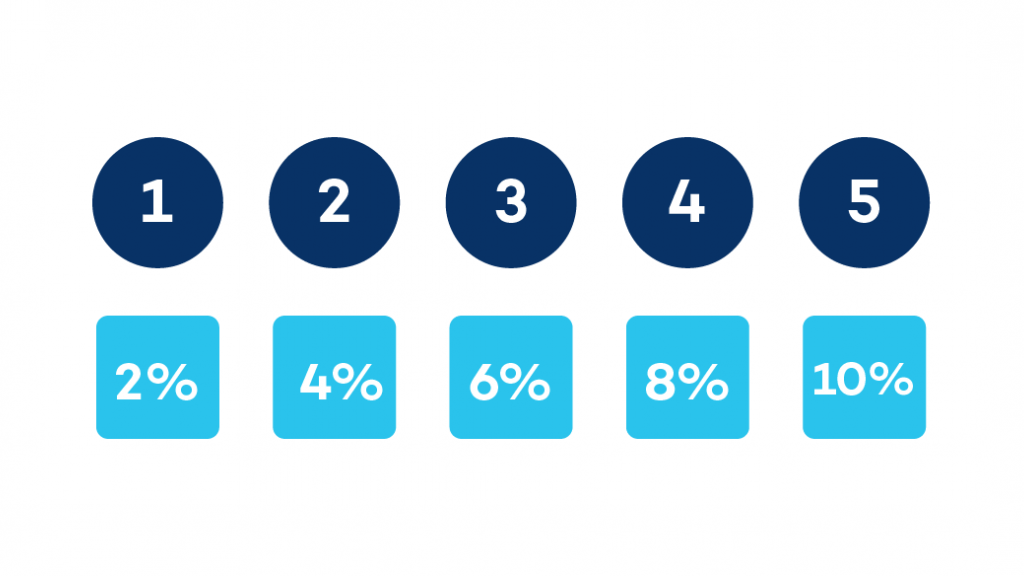

• It is an optional tool in the tendering process, whereby CO2 reduction is rewarded with an award advantage for the bidding companies. The higher the ambition level of the company, the higher the award advantage.

• It requires third-party accreditation, which lowers the burden on procurement authorities to verify that companies are doing what they say they will do in their bids.

• The CO2 Performance Ladder has been developed and used in compliance with the European Union (EU) Procurement Directive, making it immediately applicable in other EU countries.

In 2021, IISD began a collaboration with SKAO (funded by the IKEA Foundation) to scale the uptake of the CO2 Performance Ladder beyond the Netherlands. The goal of the project is to identify potential pilot projects in other European countries (apart from Belgium, where pilots are already underway) that demonstrate the effectiveness of a tool that is trialled, tested, and ready to support governments with their carbon reduction goals. We hope that these pilot projects will further inspire other countries and regions to consider the CO2 Performance Ladder as a practical instrument for green public procurement (GPP).

Initial scoping work

In 2022, IISD and SKAO will collaborate with 10 European countries to identify the building blocks required to implement and use the CO2 Performance Ladder. This scoping work was initiated based on our quick scan, which included a review of countries’ broad situations with regard to GPP implementation, their enabling policy environment, recent progress on low-carbon infrastructure, and geographic locations. Alongside these 10 countries, SKAO is exploring possibilities for the CO2 Performance Ladder in France and Luxembourg, on the basis of existing connections between those countries and the pilot programme already running in Belgium.

1. GPP frontrunners

Europe’s Nordic countries are generally advanced in GPP, specifically in low-carbon procurement. We will explore the extent to which contracting authorities in Denmark and Sweden may find the CO2 Performance Ladder complementary to their ongoing efforts to lower carbon emissions in the construction of public works.

2. Large European economies with a GPP track record

GPP has been gaining prominence across Europe. We are looking at Germany, Austria, Spain, and Italy to highlight some of the different approaches to GPP implementation, as well as capture the challenges and opportunities, in large EU economies. For instance, GPP efforts have been mostly decentralized in Germany and Spain, whereas they have been more centralized in Austria. Exploring different governance approaches to GPP and carbon mitigation activity across Europe may provide insights into how the CO2 Performance Ladder can have the greatest value and impact.

3. New policy space for GPP countries

The United Kingdom and Ireland currently have quickly evolving policies for GPP activity, specifically related to low-carbon procurement. Ireland has announced the National Action Plan on Green Tenders and the upcoming Circular Economy Bill, and the United Kingdom has introduced the National Procurement Policy Statement (2021) and upcoming procurement reforms. While these countries already have experience with GPP, more effective policy action on procurement as a driver for low-carbon development may be further leveraged with a tool like the CO2 Performance Ladder.

4. GPP ambition countries

The GPP policy space in Slovenia and Poland demonstrates political willingness to use GPP as a driver for low-carbon development—with recent initiatives such as the Care4Climate Project and the Green City and Climate Action Plan (GCCAP), respectively. In these countries, the CO2 Performance Ladder could be positioned as a tool for scaling up GPP efforts and driving low-carbon infrastructure procurement at national or subnational levels.

Observations on the status of GPP in Europe

More and more mandatory GPP

Through its Most Economically Advantageous Tender (MEAT) process, the 2014 Public Procurement Directive has made it possible to procure goods, services, and infrastructure based not only on the lowest-cost criterion but also considering other features, such as quality, innovation, social characteristics, and life-cycle costs.

However, increasingly, European countries and subnational governments are making GPP mandatory. In Austria, Finland, Germany, Norway, the Czech Republic, Italy, Spain, Cyprus, and the United Kingdom, GPP is mandatory for central government procurement. In a subset of this group—Norway, Czech Republic, Cyprus, and Italy—GPP is mandatory for all levels of government. Mandatory GPP is implemented in different ways but could oblige the procuring authority to use minimum GPP criteria in all tenders, oblige procurers to give preference to the most environmentally friendly bid, or mandate the incorporation of life-cycle analysis and/or quality considerations.

There are some other noteworthy updates. In Ireland, the incorporation of green criteria will be mandatory in all public procurement from 2023 onwards. In Croatia, GPP becomes mandatory in central procurement “where feasible” in 2022. In Switzerland, from 2021 onwards, public authorities are obliged to award tenders based on consideration of the most “advantageous” tender—not the most “economically advantageous” tender—and to consider price and quality equally in their procurement. Interestingly, another country outside of the EU, the United Kingdom, is planning similar revisions to procurement legislation in the future, transitioning from a MEAT to a MAT—the “Most Advantageous Tender”—approach in awarding contracts in order to give more flexibility to qualitative and sustainability objectives.

In many other countries in Europe, GPP is mandatory in certain product and service categories only. Some of the mandatory GPP categories include Denmark (wood products), Estonia (furniture, cleaning products, IT), Slovenia (buildings, roads), Latvia (street lighting, food), France (energy efficiency, waste requirements), Greece (transport, road lighting), Malta (office buildings, roads) Slovakia (roads), and Norway (construction, food catering). Lithuania has another approach, where GPP must account for an increasing share of public procurement, aiming for 100% from 2023 onwards.

Wide variations in implementation levels

GPP is voluntary for public authorities in the European Union. Across Europe, there are wide variations in levels of GPP implementation, as well as in levels of ambition. In some countries, such as Poland, Romania, and Slovakia, less than 5% of public sector contracts include any kind of GPP criteria. Desk-based research revealed little to no GPP activity in countries such as Bulgaria and Romania (though language barriers may have impeded getting a fuller picture). Similarly, while other countries may demonstrate a higher share of contracts using GPP, its application can be limited to minor spend categories such as office paper or cleaning products. While all efforts to incorporate GPP are worthwhile, the scale of the environmental and climate challenges will require greater efforts in the years ahead.

At the same time, there are national or local governments blazing very ambitious GPP trails, and some with an explicit focus on reducing carbon emissions. In Norway, they are focusing on completely decarbonizing the transport and construction sectors; Spain has the Carbon Footprint Registry for public procurement; Germany uses Environmental Product Declarations; and Sweden regularly uses a wide range of sustainability criteria and LCC tools in procurement. These few examples from our database will hopefully soon become more commonplace in procurement, especially in carbon-intensive sectors. Compiling lessons learned from successful and unsuccessful attempts to lower carbon emissions in public procurement will be extremely valuable for countries currently scaling up their efforts.

Cities that stand apart

It should be mentioned that, in many cases, cities stand out for their advanced GPP activities at a municipal level. Oslo has ambitious “zero-emission construction sites”; Helsinki has projects to advance climate neutrality through public procurement; Copenhagen has rigourous standards for construction and civil works; and Stockholm set a goal to become the European leader in sustainable public procurement in the coming years. Outside of the Nordic region, the city-states of Berlin, Hamburg, and Bremen have made GPP mandatory, as have the cities of Vienna and Barcelona. Recently, Tallinn won the 2023 European Green Capital City Competition based in part on their use of environmentally friendly public procurement.

Monitoring GPP activity: A common challenge

Across Europe, governments are finding it challenging to monitor and report on GPP activity systematically. For most countries, a rough indication of GPP as a percentage of total government procurement is usually available, deduced from information on e-procurement platforms such as the number of contracts awarded that include some environmental criteria. Beyond that, however, there does not seem to be systematic data collection, aggregation, or reporting on, for example, avoided carbon emissions or avoided waste for even the most advanced or “frontrunner” GPP countries. While further research is needed to understand the nature of the challenge, it likely comes at least in part from the difficulty of finding shared baselines and indicators across many levels of government. This should be an area of focus for the GPP community in the coming years, as it will also represent an important way for governments to report against their commitments to international agreements such as the Paris Agreement or the Sustainable Development Goals.

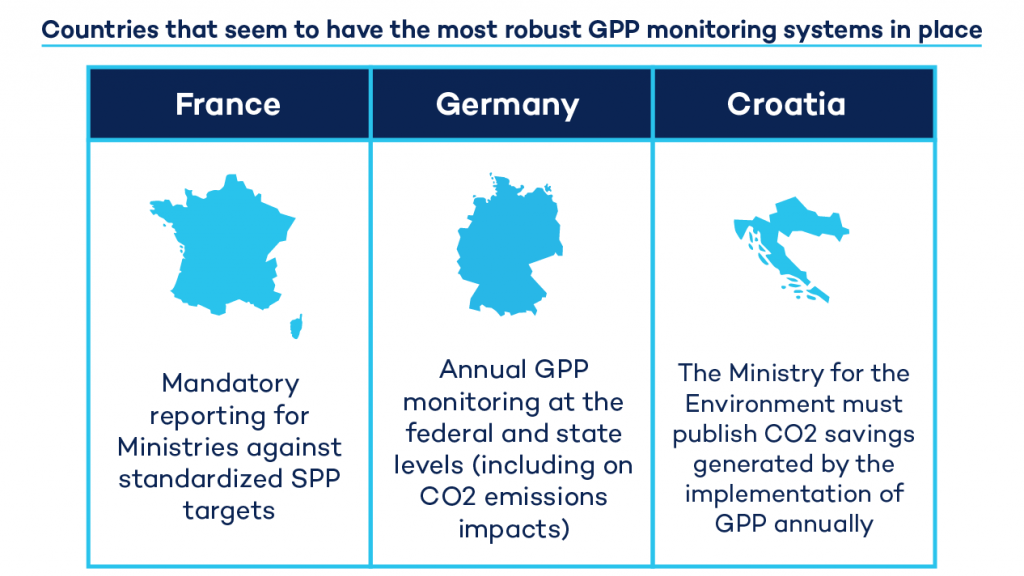

Countries that seem to have the most robust GPP monitoring systems in place are France, which has mandatory reporting for ministries against standardized sustainable public procurement targets; Germany, with annual GPP monitoring at the federal and state levels (including on CO2 emissions impacts); and Croatia, where the Ministry for the Environment must publish CO2 savings generated by the implementation of GPP annually. These might be countries to look to for inspiration and good practices on GPP monitoring and reporting, particularly for carbon, moving ahead.

Plans to improve GPP monitoring and reporting are already foreseen in Ireland, Greece, and Malta in the next few years.

Opacity regarding uptake of GPP tools

Our desktop research revealed a plethora of GPP tools across Europe that are available to procurement authorities. The most common tools referenced are life-cycle costing-based tools or calculators, International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards, and sector/product-specific GPP criteria (either the EU GPP criteria directly or bespoke GPP criteria at the national or subnational level). Other tools mentioned include other carbon footprint tools, Environmental Management Systems, eco-labels for specific categories of products or services, Environmental Product Declarations, and Environmental Spend Analysis .

Apart from citing the existence of these tools in policies or action plans on GPP, however, it is difficult to discern how often these tools are used, at what stage of the procurement process, and their specific applications to infrastructure procurement. Procurement authorities may also still be searching for the most appropriate tools to use to meet their needs. As such, in the next phase of research for this project, IISD and SKAO will work with procurement agencies at national or subnational levels, as well as with buyer networks and other stakeholders, to understand the use of GPP tools in practice and the value added of the CO2 Performance Ladder in implementing GPP across Europe.

If you are interested in learning more about the CO2 Performance Ladder or would like to pilot it in your jurisdiction, contact us! We are keen to explore options for how the tool can add value to your Green Public Procurement journey

You might also be interested in

The CO2 Performance Ladder as a Tool for Low-Carbon Procurement

This study explores the potential to use the CO2 Performance Ladder as a green public procurement tool in 10 European countries.

FAQ: Legal Considerations When Using the CO2 Performance Ladder in Public Procurement

This report answers frequently asked questions about the legal aspects of using the CO2 Performance Ladder as a green public procurement tool.

How Can Voluntary Sustainability Standards Drive Sustainability in Public Procurement and Trade Policy?

The growing use of sustainability standards in public policies is a promising trend, so long as small-scale farmers and businesses are not left behind.

Gender Equality at the Heart of Recovery: Advocating for Gender-Responsive Procurement in Ukraine

Ukraine is already preparing for reconstruction, which will cost an estimated USD 411 billion and take at least 10 years. The integration of gender considerations into public procurement processes could generate greater inclusivity in a rebuilt Ukraine.