Energy subsidies in the context of sustainable development

Editor’s introduction: in late 2009 and early 2010, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) helped prepare a Joint Report, Analysis of the Scope of Energy Subsidies and Suggestions for the G-20 Initiative, in partnership with the International Energy Agency (IEA), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank. The purpose of the study was to analyse “the scope of energy subsidies” and provide suggestions for the G-20’s initiative to phase out and rationalize inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption, and it was submitted to the G-20 Meeting of Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors in Toronto, Canada, on 26-27 June 2010. In this article, the OPEC Secretariat explains its findings and perspective on the role of energy subsidies and their relationship with sustainable development.

Energy constitutes one of the main pillars of any society and plays a critical role in economic and social development. The subject of energy subsidies, therefore, needs to be analysed in a proper context when considering its links to the economic, social and environmental dimension of sustainable development.

The G-20 Joint Report highlighted the complex path of decision-making that lies ahead for sovereign countries with regard to energy subsidies. They form an integral part of a range of policies used by governments to maximise welfare for their people. With this in mind, the phasing out of subsidies of any sort – and particularly the phasing out of energy subsidies – should be considered as a sovereign decision. Subsidies are fundamentally country-specific and are related to national circumstances.

Addressing the issue of energy subsidies involves resolving definitional, measurement and evaluation issues. The aim is to help design sound and equitable rules to distinguish between those subsidies that are inefficient and therefore need to be phased out, and those that should be maintained, due to their importance for achieving economic, social and environmental objectives. Cognizant of the fact that access to modern energy services is crucial for poverty eradication in developing countries, any analysis should consider that for developing countries, energy subsidies may constitute sensible instruments to alleviate energy poverty.

The G-20 reference to the term “rationalize” indicates an awareness that some energy subsidies could be retained. However, for the sub-group of subsidies that are deemed necessary for rationalization in the medium-term, care should be taken that social safety networks are first put in place to minimise the hardship when subsidies are removed. Indeed, the G-20 has explicitly pointed to the need to prevent adverse impacts on the poorest segments of society in the process of reducing energy subsidies.

The price-gap approach used by the IEA in the G-20 Joint Report provides a rough measure for only one sub-set of energy subsidies – those pertaining to fossil-fuel consumption. The shortcomings of the methodology are highlighted in the report. One aspect relates to the point evaluation of fossil-fuel subsidies which is dependent on the choice of year and thus could vary considerably from one year to the next. This is especially the case given the volatility in oil and gas prices. For example, figures for 2009, due to be released later this year, are expected to show a substantially lower figure than that reported for 2008. Another reservation concerns the estimate made for countries that are well-endowed with energy resources. For this group of nations, the benchmark used should concern the cost of production rather than the international market price.

One important observation is that more efforts should be channeled into developing alternative methodologies – such as social cost-benefit analysis (SCBA) – that are more suited to capturing the complexity of the decision-making process regarding subsidies. SCBA has the advantage of examining energy subsidies in a broad developmental context that evaluates the impacts of energy subsidy changes on social welfare.

It is very important to look at the complete picture when it comes to discussing and analysing energy subsidies. In this context, it must be stressed that non-fossil-fuel energy subsidies are considerable in number and have been increasing over time. In fact, on a per unit basis, subsidies relating to renewables, biofuels and nuclear energy are estimated to be much greater in number than those relating to fossil fuels.

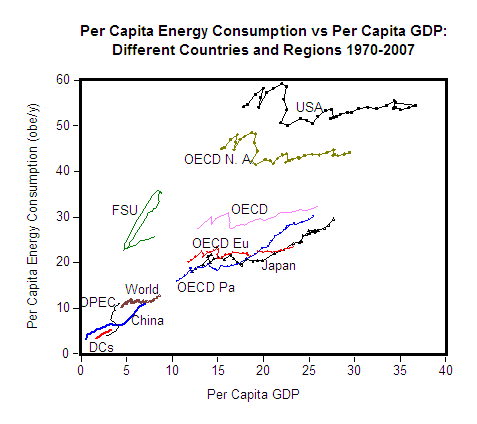

The energy subsidies discussion usually relates to the environment. It is often concluded that developing countries, particularly, need to improve their use. This is difficult to understand when examining the per capita energy consumption levels compared to per capita GDP.

In addition, negative subsidies in the form of taxes on energy should not be ignored. They are mainly evident in relation to fossil-based transport fuels. The OECD estimates that during recent years, such subsidies have annually exceeded US$ 400 billion. However, including Goods and Services Tax and Value Added Tax, OPEC estimates that more like US$ 800 billion has been realized annually through petroleum product taxation in the OECD region alone (more detailed analyses on selected OECD countries can be found in http://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/archive/WGW2009.pdf). These taxes significantly affect end-use relative prices for fuels.

The overriding priority of developing countries is to enhance economic and social development and to eradicate poverty. Ideally, there should be no conflict between the economic and environmental thrust. And even if the phasing out of subsidies is called upon on the grounds of climate change mitigation, it is important to emphasise that the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and its principles should apply. In particular, the principles of equity, common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities should not be ignored, nor should the already mentioned economic and social priorities of developing countries.

However, in the final analysis, individual sovereign states must decide energy subsidy policy for themselves.